Canada is experiencing a period of political turbulence that is easy to misinterpret precisely because it lacks spectacle. There have been no sweeping electoral realignments, no mass populist insurgencies, and no wholesale rejection of democratic institutions like we’ve seen in other peer countries. Governments continue to function, elections still confer authority, and leaders continue to win votes, leadership reviews, and confidence tests.

Yet beneath this surface continuity, leadership authority is being challenged. Leaders survive procedurally while struggling to retain confidence, coherence, and durability. What defines the current moment is not a single crisis, but the slow accumulation of internal fractures: leadership reviews that resolve little, caucus dissent that spills into public view, and parties that appear organizationally intact yet directionally adrift.

This dynamic unfolds against a distinctly Canadian democratic tension. Our latest research at Pollara Strategic Insights reveals a striking contradiction: Canadians strongly endorse many of the core grievances that animate populist politics—namely, distrust of elites, frustration with institutions, and a belief that politics is insufficiently responsive—while simultaneously rejecting populism as an identity, a label, or a leadership style.

The simmering instability is evident across the country, from Danielle Smith’s rocky reception amongst the party faithful in Alberta to Bonnie Crombie’s exit as leader of the provincial Liberals in Ontario to the internal disagreements constraining Québec Solidaire in Quebec to even, at the federal level, Steven Guilbeault’s dramatic resignation from Mark Carney’s cabinet.

The data

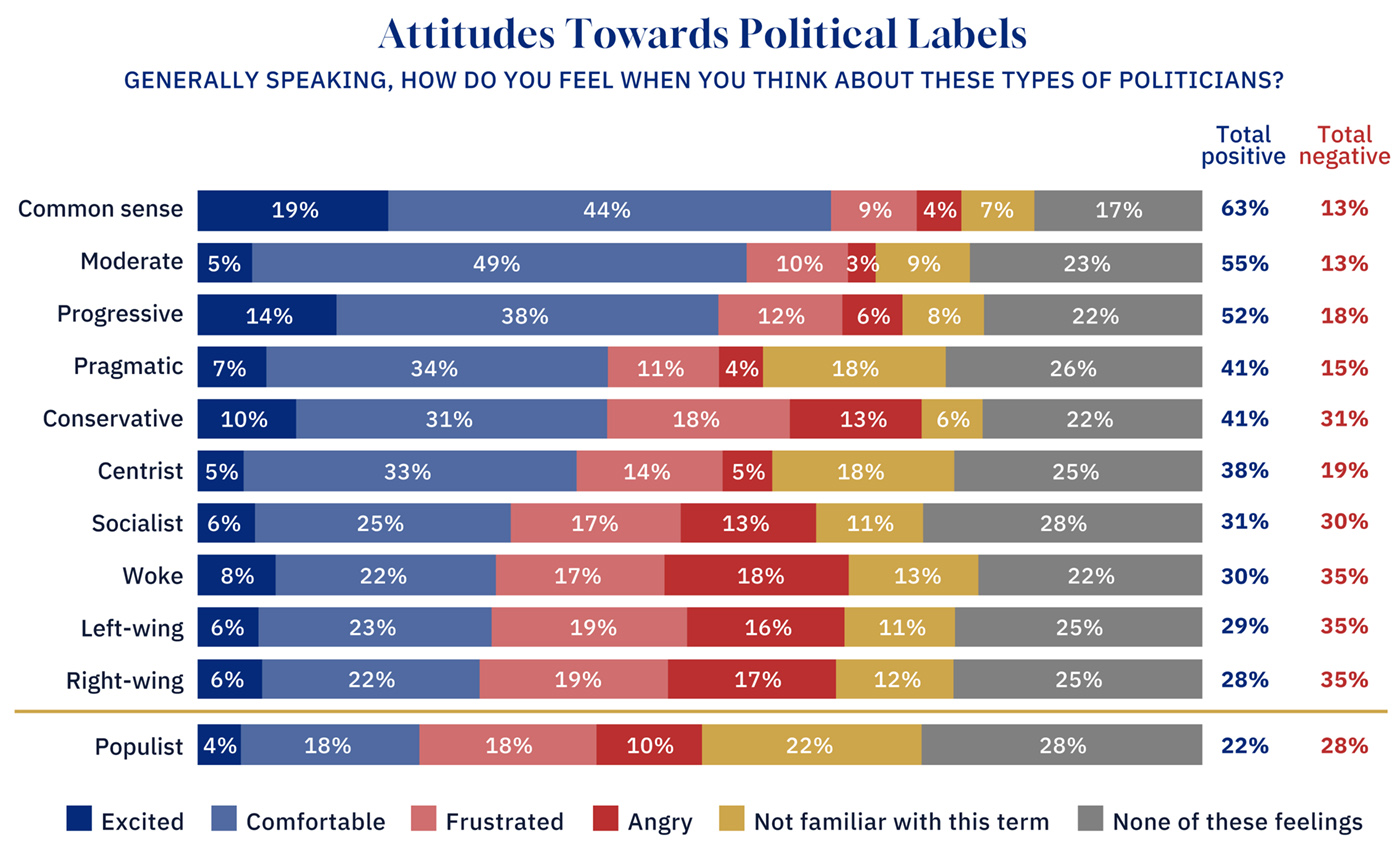

In a study conducted between October 15 and 20, 2025, with a randomly selected sample of 2,700 adult Canadians, our data show that “populist” stands apart from every other political label tested, not because it provokes strong opposition, but because it fails to generate much emotional engagement at all. Compared with ideological, stylistic, or values-based descriptors, populism elicits weaker positive reactions, only middling negative reactions, and unusually high levels of unfamiliarity or detachment.

Source: Pollara Strategic Insights. Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Looking first at positive reactions, only 22 percent of Canadians report feeling either “excited” (4 percent) or “comfortable” (18 percent) when thinking about politicians described as populist. This is the lowest total positive score of any label tested. Even labels that generate controversy perform better on this metric: “right-wing” politicians register 28 percent positive; “left-wing” 29 percent; “woke” 30 percent; and “socialist” 31 percent. More mainstream descriptors perform far better. “Common sense” leads the field with 63 percent positive; “moderate” scores 55 percent, and “progressive” 52 percent, while even “pragmatic” and “conservative” each attract 41 percent positive sentiment.

Negative reactions to populism are also comparatively muted. Combined feelings of “frustration” (18 percent) and “anger” (10 percent) yield a 28 percent total negative score, placing populism well below labels such as “woke” (35 percent negative), “left-wing” (35 percent), “right-wing” (35 percent), “conservative” (31 percent), and “socialist” (30 percent). These ideologically charged terms provoke sharper emotional backlash, particularly anger: “woke” politicians, for example, generate 18 percent anger, compared with just 10 percent for populists.

What most clearly distinguishes populism, however, is disengagement and uncertainty. Fully 22 percent of respondents say they are not familiar with the term “populist,” the highest unfamiliarity score of any category tested. No other label comes close: unfamiliarity ranges from just 6 percent for “conservative” to 13 percent for “woke.” In addition, 28 percent say that none of the listed feelings apply when they think about populist politicians, again one of the higher levels of emotional neutrality in the dataset.

Source: Pollara Strategic Insights. Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Together, “unfamiliarity” (22 percent) and “emotional disengagement” (28 percent) account for half of all responses to the populist label. The results suggest that populism in Canada operates more as an abstract grievance language than as an emotionally resonant political identity.

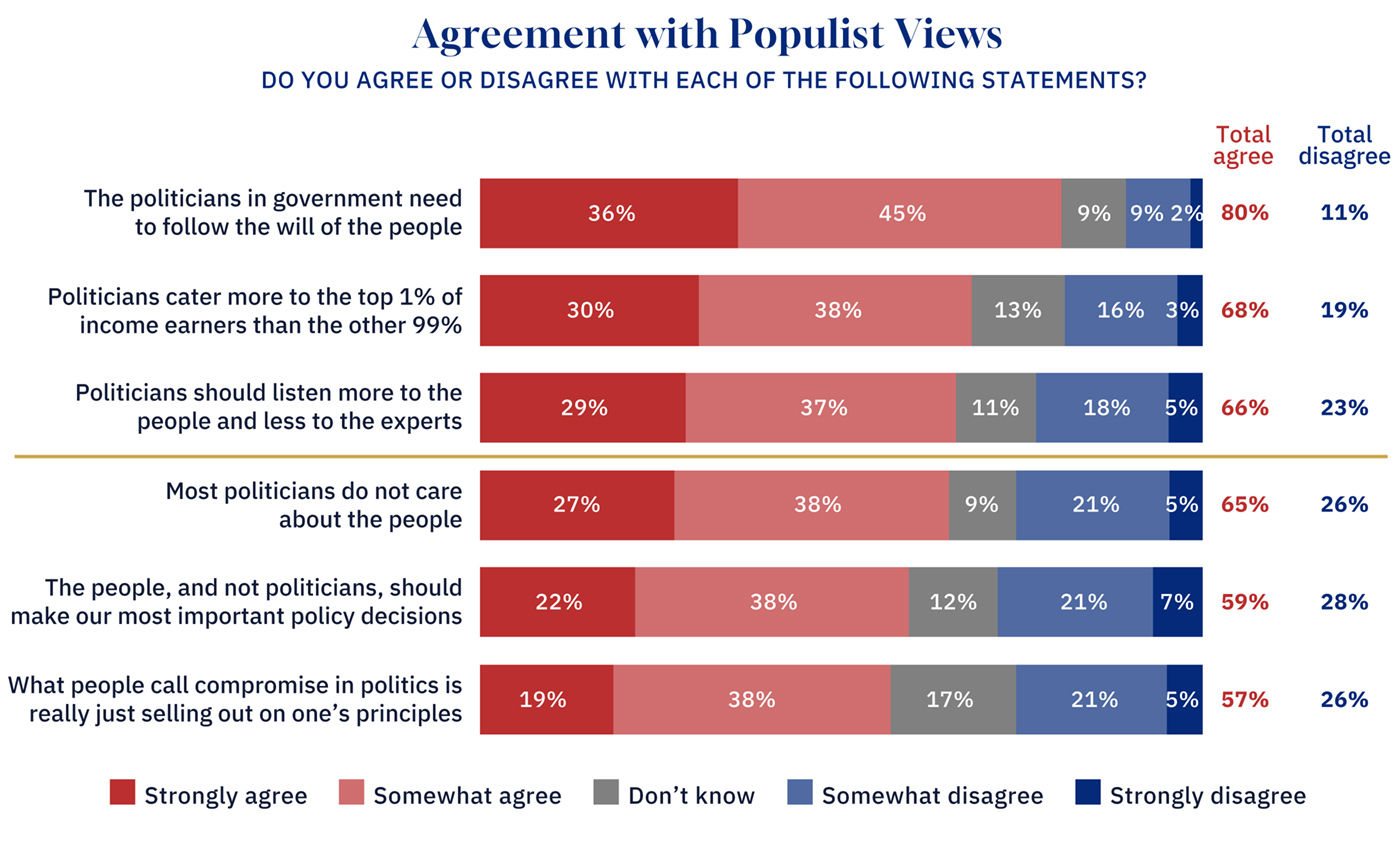

Yet this resistance to populism as a label contrasts sharply with widespread endorsement of populist democratic claims. Fully 80 percent of Canadians agree that “Politicians should follow the will of the people.” Sixty-eight percent believe “Politicians are overly influenced by the top 1 percent.” Two-thirds think “Politicians listen too much to experts and not enough to ordinary citizens,” while 65 percent believe “Politicians do not genuinely care about the public.” Nearly 60 percent say that “The people—and not politicians—should make the most important policy decisions,” and 57 percent regard compromise as a “form of selling out.”

These attitudes reveal a deep pool of frustration and unmet expectations, even as Canadians remain reluctant to embrace the populist identity explicitly.

Lessons from history

At first glance, this ambivalence appears surprising given Canada’s deep populist roots, but history may help explain contemporary attitudes. From the agrarian revolts of the late 19th century to the United Farmers movements of the early 20th century particularly in Western Canada, populist movements have repeatedly surfaced to challenge entrenched power.

Federally, the Progressive Party gave voice to rural and regional grievances against Liberal and Conservative elites. During the Great Depression, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation fused agrarian protest with labour activism and social democratic ideals, demonstrating most notably through Tommy Douglas’s introduction of Medicare in Saskatchewan how populist pressure could be translated into lasting institutional reform.

View reader comments (4)

Social Credit, emerging in Alberta and British Columbia, represented a parallel populist tradition rooted in monetary reform and a moral critique of financial elites.

The Reform Party, founded in 1987, marked the most recent major wave. Born of Western alienation and resistance to centralized federal power, it championed direct democracy, Senate reform, and fiscal restraint. Its rapid ascent and eventual absorption into the Conservative Party once again illustrated a recurring Canadian pattern: populist movements rarely govern as populists.

Instead, unlike in Europe, where populist parties often remain distinct and oppositional, they are absorbed, moderated, and normalized within existing institutions, their sharper edges blunted by the demands of governance. In the process, the explicit populist label faded in Canada, even as the expectations it produced endured.

Takeaways

Taken together, these patterns define Canada’s distinctive condition of populism without populists: a democratic tension between demand and acceptable political expression. Canadians articulate strong grievances about elite unresponsiveness and systemic unfairnes, and yet resist leaders who adopt the rhetorical and stylistic markers of populism seen elsewhere. The appetite is for accountability and renewal, not for theatrical confrontation or institutional disruption.

For political leaders, this configuration creates a subtle but consequential hazard. Self-identifying as populist offers little reward and significant reputational risk. Canadians overwhelmingly reject figures who embody the style of American right-wing populism. At the same time, the grievances that animate populist movements elsewhere, such as distrust of elites, dissatisfaction with institutions, and perceptions of distant and unresponsive governance, are unmistakably present.

Despite this aversion to populism as a label or style, recent political developments demonstrate that Canadian politicians are increasingly being held accountable by electorates animated by populist expectations around transparency, fairness, keeping promises, follow-through, and genuine influence. Leadership challenges, caucus revolts, and relentless scrutiny signal tensions between authority and responsiveness.

This is the inconvenient democratic reality confronting Canada’s political class. Politicians of all stripes are being held accountable by voters who expect to be heard, respected, and acted upon. Parties should be reminded that in the end, those who govern must answer to those who elected them.

Why do Canadians reject the 'populist' label despite holding populist grievances?

How does Canada's historical experience with populism explain its current political landscape?

What is the 'inconvenient democratic reality' facing Canadian politicians today?

Comments (4)

There is absolutely no evidence that the Canadian electorate have any expectations of transparency or accountability. We have had over ten years of the most corrupt and least transparent government in our history with no end in sight. Canadians have shown themselves to be gullible and susceptible to a slick hairdo and a shiny suit in the pursuit of free stuff. They will believe anything, as long as you tell them that you’re going to spend more of their money than the other guys.