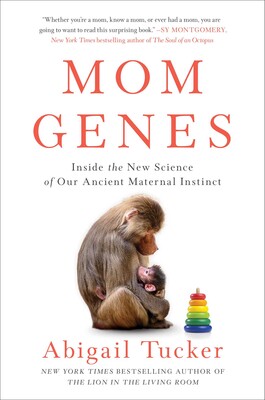

In this Hub Dialogue, The Hub’s editor-at-large Sean Speer speaks to Abigail Tucker, the author of Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal Instinct, about the science behind our maternal impulses.

This conversation has been revised and edited for length and clarity.

Sean Speer

Abigail Tucker is a science writer, a correspondent for Smithsonian magazine and a best-selling author. Her latest book Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal Instinct was published in April 2021.

Mom Genes is already widely acclaimed. Reviewers have called it “fascinating,” “intriguing,” “deeply researched,” and “eye opening.”

We’re honoured to have Abigail join us for a Hub Dialogue to talk about why she wrote the book, what she learned along the way, and what she means by “Mom Genes.”

Thank you so much for speaking to us today, Abigail.

Abigail Tucker

Thank you so much for having me.

Sean Speer

The physical manifestations of pregnancy and motherhood are generally well known. Society makes jokes and tell stories about pregnancy cravings, weird maternity clothes, or the extraordinary efforts that women go through to lose their pregnancy weight. But we don’t talk much at all about the various unseen ways in which pregnancy and motherhood can have deep chemical, neurological and physiological effects. Why do you think that’s the case?

Abigail Tucker

I think that it’s funny how we, as a culture, just kind of bury the lede a little bit, and we focus on all these freakish external transformations, when really the most interesting parts of the maternal transformation are in the brain.

After doing all my research and visiting these labs, where they study the transition to motherhood among mammals, especially humans, I came to the conclusion that the brain is arguably the most important organ of childbirth, even though it’s sort of the last one that comes to mind. It’s not really top of the list when you go into the labour and delivery ward. But I think it’s just that the body stuff is so weird and it’s so visible in a way, that it’s easier to talk about than these hidden things.

Sean Speer

You mentioned in the book that a friend once told you that having a baby “felt like she grew a new heart.” It reminds me of a common line from New York Times columnist David Brooks in which a friend of his said that when she had her daughter she discovered that: “I loved her more than evolution required.”

It’s a wonderful formulation, but your book suggests it’s not quite right. That there is actually something evolutionary about how parents in general, and moms in particular, feel about their children. To what extent are these figurative expressions actually real and scientific?

Abigail Tucker

Well, what struck me about the “growing a new heart” quote from my friend was that there is fascinating research about how the baby’s cells and pregnancy trespass across the placenta into the mother’s body, and integrate with the tissue of her body, including her heart tissue.

In particular, there’s cool research from a lab at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, where they study how multipotent fetal cells may actually help adult women to regrow heart cells and survive cardiac trauma like heart attacks. So that said, there is like a literal truth to these treacly things that mothers say to each other. I should say that these fetal cells also trespass to the brain, and there’s ongoing research about what they might be doing there to maintain the maternal mind. I think, in general, we’re designed to be bowled over by love for this helpless organism that suddenly demands self-sacrifice from us.

I will say though that in the darker corners of this research, you do learn that as powerful and biologically-rooted as the impulse toward maternal self-sacrifice may be, it’s not as absolute as we might like to think that it is. There are environmental disturbances that can occur, that can shake this feeling that so many of us in modern America and modern Canada take for granted. And I think that’s really provocative too.

Sean Speer

Abby, your research shares all of these extraordinary insights about motherhood that we barely notice, but yet might have evolutionary biology origins. Take, for instance, that most mammals carry their babies on their left side. Or that women pregnant with boys tend to be more nauseous. What’s the most interesting or unexpected insights that you discovered in your research?

Abigail Tucker

There were so many crazy things that came up. I have four kids, and so, I was selfishly interested in what’s called child effects: the way that particular children influence their mothers. I just became really interested in how I personally changed in relationship to all four of my kids — three girls and one boy.

But one interesting thing that came up that is sort of another layer on top is how the environment, and particularly the stresses that mothers feel in their environment, can suddenly influence whether or not you have a boy or a girl in the first place. I was just floored by this research showing that after national traumas like 9/11, there are subtle but measurable upticks in the numbers of girls born. There’s also not as well established, but still interesting, research showing that after events of so-called “national jubilation,” things like World Cup matches or victories, there’s also a subtle uptick in the number of boys born. The theory being that boys are heavier and more difficult to gestate, so they’re more likely to survive in utero when women are getting positive signals about their situation and the world.

As a mom, there’s a way in which you think of yourself as being a powerful being, because your word, at least in theory, is sort of law for these little people underfoot. Yet I was just so interested in the ways that all of these subtle forces shape moms as we develop as organisms, and how we are subject to the whim of so many things – from what our kids are up to, the nature of our relationship with our own mother, to our diet and financial outlook and social network – all these million variables. When you hear the word “maternal instinct,” it’s sort of sounds like “we’ve got it, we’ve got the maternal instinct, we’ve got it made, we know what we’re doing.” When really, I think that the story of the book is that nothing could be further than the truth and that moms are at the mercy of many forces, and that it very much behooves us to understand these forces.

Sean Speer

In a sort of separate but related area, the book investigates the effects of motherhood on both biological and adoptive mothers. While there are obvious differences, you find that even adoptive mothers can experience physical changes associated with being a mom. Do you want to just elaborate a bit on what you found with respect to adoptive or foster parents and how motherhood can change them as well?

Abigail Tucker

One of the coolest things that I did was visit this lab at New York University, where they basically manufacture mothers using laboratory rodents like mice and rats.

They do it in three ways. First, the old-fashioned way: you can just let little male and female rats hang out together and see what happens next.

Second, if you as the scientist wants to be in charge of this situation, you can inject these virgin rats and mice with a cocktail of various hormones related to childbirth and pregnancy, like oxytocin, dopamine and estrogen. That’s the way you do it chemically.

And the third way you do it is like this: you take a female rat or mice, who’s never been around babies before, and put her in a cage with a biological mother and her babies. The female rat isn’t so happy for awhile. But after about a week, the virgin female starts to change, and she starts to demonstrate maternal behaviour. She starts to retrieve the rat babies when they cry, she doesn’t run away from them, and performs nest-building behaviours. If you were to look inside her brain, scientists have also tracked changes that are happening on the level of cellular growth, that her brain is routing new receptors and changing in different ways, in the way that a biological mother’s might.

Similarly, humans can become mothers in different ways. Pregnancy and childbirth makes the transition happen radically and absolutely. But when we humans make the decision to take on a child and hang out with that child, even if we didn’t physically give birth to that child, it stands to reason that our brains are going to change over time. Maybe it takes a little bit longer than it does for the biological mom with her sudden burst of euphoric hormones during childbirth. But sure enough, that adoptive mom brain is going to change over weeks and months, in a way that will support this new relationship, which is her new reality. So I found that to be totally crazy: that first of all, there are labs in the world where scientists are just concocting mothers left and right, and then also the fact that you can make them in multiple ways.

Sean Speer

I’m a new dad. Our son, EJ, is just about six months old. What does your research tell us about the effects on dads?

Abigail Tucker

First of all, I should first explain one thing that I didn’t initially understand — and I honestly think this is because I’ve watched too many Disney movies with my children, like the Lion King and Bambi, where there’s all these highly, anthropomorphized mammal dads hanging out and taking care of the babies. For the most part, this is a fairy tale, as mammalian paternal care is extremely rare. Only 5 percent of all the mammals, all of our furry friends that come to mind when we think of them, have any dad involvement at all. So, in that way, human dads are already the great heroes of the animal kingdom. They’re sort of amazing and superior in so many ways.

I think the research shows that dads, if they are given the chance and have the will, can transform into maternal beings, or acquire the paternal version of the maternal instinct. There really is the same kind of core seed inside the brain. If they’re given that chance to rise to the occasion, and they’re willing to do it, then they can also transform in profound ways: their brains can come to look somewhat like mom brains.

But we can also acknowledge that there’s a lot more of a spectrum of paternal behaviour that we see in typically see in moms — from zero involvement and in turn zero transformation all the way to full blown metamorphosis. There have been some really interesting studies in two-father families, for instance, that show that those dads’ brains, in particular, more closely resemble biological moms’ brains. That’s probably because these guys are just so much in the trenches doing all the child-rearing stuff. Again, it’s that thing where there’s this kernel inside of the mammal organism that, with the right exposure, can grow.

In the lab, they can also invent dads by either injecting rats and mice with hormones, or by letting them hang out with babies. But generally for males, you need a lot more hormones, and extra time rooming in with the babies to make that transformation happen. It’s unclear what exactly is it about being around the mom and the baby that’s triggering the dad and causing him to change. There was a really cool recent study showing that it might have something to do with the smell of pregnant women, and it begins to change men’s perception of infant faces and things like that.

Sean Speer

One of the areas of focus at The Hub is issues of public policy and governance. As you carried out your research, understanding that the Canadian context and American context may be slightly different, are there any public policy implications that struck you? Anything that policymakers ought to be doing to better support moms and families with young children?

Abigail Tucker

I should start off by saying that while I’m still not totally sure why this is, I can’t quite get a straight answer, many of the most exciting labs and the most accomplished scientists studying maternal behaviour are Canadian: either working in Canada or Canadian citizens working in America. That was really interesting to me.

As for the broader public policy applications of this research, they are so huge. The most important thing is how stress can warp the maternal brain and almost stunt, in a way, these natural transformations. Scientists are able to document neurological changes over the nine or ten months of pregnancy. If you take women and put them in brain scanners before and after pregnancy, you can actually see their brains begin to change. There’s a similar phenomenon with rats.

While we can’t stress human moms out as much as lab rodents even if some scientists would like to learn what happens to us, studies in rats have found that constant chronic stress can stop the maternal brain’s standard transformations from happening.

That means that the best thing that we could do for moms is to shore up their social support system, through all kinds of creative ways. Doing things like not just giving maternity leave, but maternity leave that starts before the end of pregnancy, so moms can have like a month to get their bearings, get everything ready, and reduce stress.

Paternity leave has also been shown to reduce drastically the amount of anti-anxiety medications that new mothers need. So, that’s sort of the biggest red-letter issue to me, but it can also take really small forms.

Here in Connecticut, the Yale Child Study Center looked to find the single environmental factor that was most correlated with postpartum depression in new mothers, and that factor turned out to be the lack of access to disposable diapers, which strikes me as an easy problem for an outerspace -traveling species like ours to solve together. But for individual poor women it is this huge, insurmountable thing and a chronic source of stress, because you can’t use food stamps to buy diapers. So that’s a simple thing, if we could just take off from the table this one stressor, then we would reduce the amount of women who need psychological health and support. Postpartum depression is totally devastating, not to mention expensive to treat once it takes hold.

There are countries in Europe that are light years ahead. In some countries, they have state funded baby nurses that will go home with new mothers and help them for weeks after they give birth. And that’s another thing: if you look into these labs that study monkey mothers, how they’re placed in the social hierarchy; their relationship with other monkeys and feelings of status and security inside the broader group, these are key triggers for mothers that frame their relationship with their infant. Well, for humans, if there’s an isolated, young mother who doesn’t have anybody to help her, that’s something that government can step in and do. And we don’t always have to wait for the government to help either. Doing a simple thing like checking in on a neighbor who had a new baby, or just visiting a sister who’s had a new child, and expressing your support for her in palpable ways, is really better than medicine sometimes.

Sean Speer

That’s really powerful. If I can ask one final question: I’ve heard on a podcast that you personally have some Canadian roots. What’s your connection to Canada?

Abigail Tucker

My relatives are from Ottawa and Newfoundland, and my dad came to America as a child. So we’ve always had very strong, pro-Canadian sentiments in the family. I actually have never been able to figure out if I’m eligible for citizenship, but if I am, I’m going to get it someday. It’s a life goal.

Sean Speer

Well, thank you for participating in today’s Hub Dialogue, Abby. It’s been a fascinating conversation.

The book is Mom Genes: Inside the New Science of Our Ancient Maternal Instinct, and it’s full of interesting research, ideas and insights about pregnancy and motherhood, and the science behind the maternal instinct.

Thank you so much, Abby. It’s a real honour and privilege to be able to speak with you.

Abigail Tucker

Thank you so much for having me.

Recommended for You

Fred DeLorey: Why real Christmas trees matter more than ever

Ray Pennings: A good Christmas reminder for Canada’s leaders: Religion is a public good

Sean Speer: Canada needs to kickstart its cultural policy

Kelden Formosa: JD Vance is right. Anti-Christian bigotry in Canada shouldn’t simply be waved away