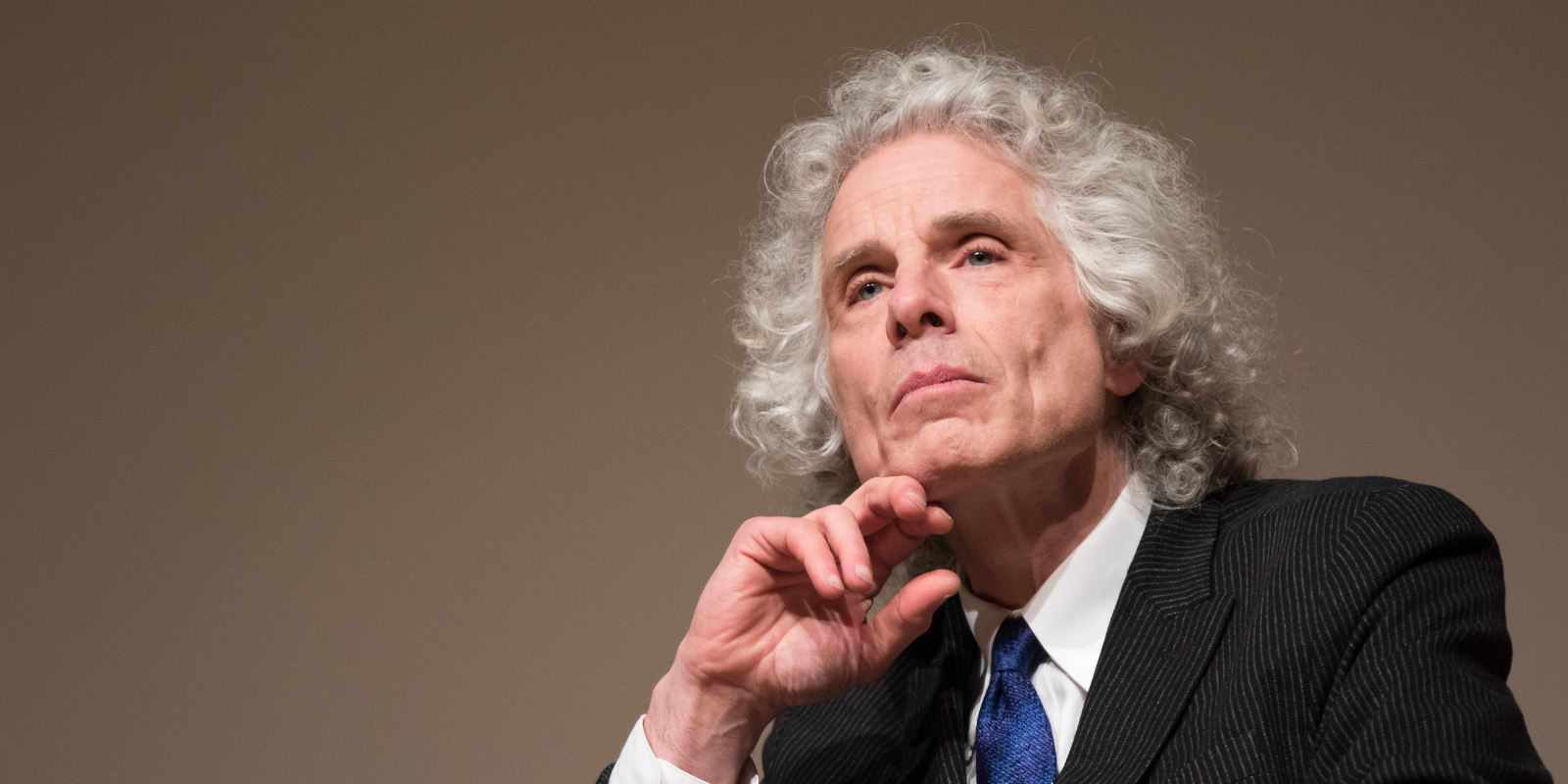

Today’s Hub Dialogue is a conversation between The Hub’s executive director Rudyard Griffiths and world-renowned cognitive scientist Steven Pinker about rationality and how our move towards political and social tribalism is threatening our collective commitment to objectivity and truth.

Pinker is the Johnston family professor of psychology at Harvard University and is the author of many massively popular books, from Enlightenment Now to his latest bestseller Rationality. Foreign Policy Magazine credits him as one of the world’s top 100 public intellectuals.

This conversation has been revised and edited for length and clarity.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Steven Pinker, great to be in dialogue with you again.

STEVEN PINKER: Nice to see you, Rudyard. Thank you for having me.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Well, let’s take advantage of the fact that not only have you written a book on rationality, but you’ve taught a course at Harvard about it. This is a real blessing to us to try to get some first principles on the table here. As we struggle, frankly, I think in our society in this moment to understand what rationality is and the value of it to our individual and collective lives. So maybe you could just begin by giving us your definition of rationality. What is this? How should we think of it? Let’s get practical to start.

STEVEN PINKER: I define rationality as the use of knowledge to attain goals. Knowledge is conventionally defined by philosophers as justified true belief. And in practice, the way you use knowledge to attain goals is to employ implicitly or explicitly one of the normative models of rationality that have been worked out over the centuries. Logic, probability, critical thinking, the theory of rational choice, the distinctions between correlation and causation. All the kinds of things that we try to formalize when we take university courses, but there are, are based on intuitive notions of what gets us what we want in the world.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Okay. You know the argument well. There’s those out there that say that we have these caveman brains and we’re running around driven by instinct, by irrationality. What’s your response to the caveman brain argument? Because I think that grips a lot of the ways that people are thinking now about the extent that we are irrational. We are prone to an inability to reason.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. So I am an advocate of trying to understand human nature in an evolutionary framework, particularly in my book, “How the Mind Works”. But I begin “Rationality” with an argument that we shouldn’t blame our current craziness on our hunter-gather ancestors. Because in fact, what makes homo sapiens such a weird species is that we, and by we, I mean, everyone, including the cavemen deploy an awful lot of cause and effect reasoning of logic of probability to eeking out in existence from an unforgiving environment. And the first few pages of the book describe how the San of the Kalahari Desert formally called the Bushman, but one of the most recent surviving hunting and gathering people. They use an awful lot of rationality. It isn’t just a question of running away from lions. That’s what antelopes do, but we’re not antelopes. Our ancestors killed and ate antelopes because we outsmarted them.

What the San do is they engage in persistence hunting, which means that they take advantage of the human ability to deal with heat because we’re naked. We are good marathon runners, we’re upright. So even though other mammals are faster than us, we can outlast them. Eventually, they’ll overheat, they’ll keel over of heatstroke. But crucially, we could only do that since they spot a human they sprint out of sight. By tracking them based on their hoof prints and other spots left behind. And in fact, the San engage in pretty lengthy and ingenious reconstruction of, what species probably left the track? What condition is it in? What sex is it? Which way is it likely to have gone? And they invent fairly sophisticated tools and traps and poisons and snares with cause and effect reasoning.

They argue with each other, a young upstart can challenge a pompous elder. They recount superstitions, but then some of them challenge them. So it’s in our nature. Yes, we don’t innately command the theorems of logic and probability, those have to be learned in school. But we do have an intuitive sense of rationality and this question, what social institutions bring it out? Because the capacity is there.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: So, let’s move now from the individual to society. Because I think this is an interesting way to get us thinking: that rationality isn’t something that’s just embedded in the mind of the solitary actor. You see rationality in community, in institutions. This has a normative context. Am I right?

STEVEN PINKER: Exactly. One of the reasons that I defined rationality as the ability to pursue goals, is that it makes it clear that the goal of deploying all our smarts isn’t necessarily to get at objective reality. It could also be to advertise ourselves as brilliant know-it-alls, as angels with a halo over our head. Now, if each one of us deploys our smarts to do that since none of us actually is perfectly good, perfectly rational, omniscient, infallible. You can get an awful lot of fruitless argumentation as everyone deploys their best arguments as to why they’re right. And of course, not all of us can be right about everything always.

So to attain rationality at the level of society, it’s not just a question of having smart people or informed people. But we have to abide by rules of the game that allow the truth to emerge, despite the fact that each one of us wants our truth to prevail, wants our side to look good, ourselves to look brilliant. And so we have things like free speech, freedom of the press, open debate, peer review, empirical testing, fact-checking. All of the things where each of us, even though we’re all kind of biased to deploy our reasoning for our own benefit, the biases ideally can kind of neutralize each other, and over the long run there’s some hope that truth will emerge.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Okay. Well, that leads us on to where we find ourselves today. I mean, there’s a perception that we are living in a post-truth society. That the very building blocks of rationality have been removed from much of our popular discourse from indeed the very institutions that we once turned to, to create these collectively shared understandings. What’s at the root of this Steven? What’s your diagnosis for our kind of reason at this moment?

STEVEN PINKER: Well, the contributors to irrationality are in our nature, they’ve always been with us. Conspiracy theories have always been with us, they used to be worse. They went to the Holocaust and deadly ethnic riots and vigilante killings and lynchings. Quack cures and pseudoscience kind of was science until the scientific revolution, and still to a large extent is fake news. I mean, what are accounts of miracles in scripture? But the original fake news, paranormal phenomena.

In assessing our current situation, we shouldn’t imagine that there used to be a rational society and we have fallen down from it. As I like to say, quoting Franklin Pierce Adams, “The best explanation for the good old days is a bad memory.” I think now what we are seeing thanks to the rise of fractionated media, such as cable news, at least in the United States and of course of social media, is that some of the pseudoscience, the conspiracy theories can circulate widely and quickly. The mechanisms of spreading information by hyper-partisan media and social media mean that they often do an end-run around the conventional mechanism of fact-checking and truth-seeking and error correction. But we shouldn’t exaggerate to the point of saying that we’re living in a post-truth society. That couldn’t be true because if it was true, then that statement itself couldn’t be true. And therefore, we couldn’t be living in a post-truth society. That is a rhetorical flourish because there are segments of the population that stubbornly cling to a partisan belief. But to say that we’re living in a post-truth society would be hyperbole.

One way to think about it from the Canadian psychologist Keith Stanovich is that we live in a “my-side” society increasingly. That perhaps the most pervasive and robust cognitive bias is the one in which people steer their reasoning toward a conclusion that is one of the sacred values of their own tribe. Their own political party, their own religion, their own social clique. And that we tend to promote the beliefs that make us heroes within our own clique for pushing the positions that make our clique look noble and wise. And make the opposing cliques look evil and foolish.

And we have seen, particularly in the United States, a rise in polarization, especially negative polarization. A growing proportion of each side sees the other side as dangerous and evil. And that has led people to ratify the beliefs that are flattering to of their own side.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: You wrote, “People express opinions that advertise where their heart lies. As far as social media is concerned flaunting those loyalty badges is anything but irrational.” This would really grip me because it provided me at least with an understanding as to why we do what we do. And that there is self-interest here. It isn’t just simply people running off and believing in QAnon, or that the world is flat. We’re extracting something from this behavior that is important to us.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. In particular, when it comes to the more outlandish beliefs, the one that really led to the idea that we live in a post-truth society. The kooky conspiracy theories, the deep statehouses, cabal of Satan-worshiping pedophiles, that jet contrails are mind-altering drugs dispersed by a secret government program, that Bill Gates is trying to implant microchips in us through vaccines. A lot of these beliefs are not about people’s day-to-day lives, about the actual objects and social networks that impinge on them. Because even the people who endorse the kooky theories, they hold the job, they pay their taxes, they get their kids dressed and clothed and fed and off to school on time. So it’s not as if they’re completely out of touch with reality. They couldn’t be because as Philip K Dick said, “Reality is what doesn’t go away when you stop believing in it.” There are realities that just don’t really affect most of us as citizens. Why do bad things happen to good people? What is the ultimate cause of death, disease, and misfortune? What really goes on in closed cabinet meetings and the White House and at 10 Downing Street and in scientific labs? I’ll never know it, my opinion on it doesn’t really affect my life. It doesn’t affect anything. But it can make me feel good. It can make me a hero within my social group if I’m endorsing the beliefs that make my side look good and make the other side look bad.

I mean beliefs about the historical forces, political power, distant corporations, metaphysical questions, like what happens to you after you die? Does the universe have a plan or a purpose? All these kinds of cosmic, philosophical political questions, as opposed to your day-to-day life.

The idea that you should only believe things that you can prove to be true actually is a pretty exotic, unusual, weird belief when it comes to most people at most times. For people who are children of the enlightenment and believe that we can strive for the truth in all things scientific, historical, political. Then we think that our beliefs should be forged in the crucible of verification and fact-checking. But for most people, these beliefs are statements of value, statements of purpose.

So if someone says, I believe that Hillary Clinton ran a child sex ring out of a pizzeria. What are they really saying? What they’re really saying is, I think she is so heinous and evil that that’s the kind of thing she could do. And who’s to say she doesn’t. Or it’s really a way of saying, boo Hillary.

And I think you and I would be tempted to say, now, wait a second, you have every right to hate Hillary, this is a democracy, you can believe anything you want, but you don’t have the right to turn your hatred into a factual claim. If you and I believe that, and there’s a sense in which we’re the weird ones when it comes to the human species. Now, I think that is a conviction that ought to be shared. We really should base all our beliefs on evidence, logic, and consistency. But psychologically, that’s not the way people naturally work.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Another interesting takeaway from your writing and thinking on rationality is you believe that social media is not the toxic brew that exists at the center of the dysfunctionality of our discourse and our inability to reason with each other. And I’d like to hear a little … I know it’s not that you have a view of social media as an unalloyed good. But at the same time, you don’t think it should be the moral panic of our time.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. I put it maybe a little different because a lot of the rules of social media go completely against the guidelines for any institution, network, or medium that promotes truth. Because the thing is that on social media, of course, all of the rewards come from notoriety, notice, sharing, engagement, which can bring out the worst in us. So, I wouldn’t say that I’m a particular fan of social media.

But rather that I think that there’s just too much glib blaming of every social problem and political problem on social media without adequate testing and knowledge. They’re so new that we really don’t have the studies that should convince us that they are to blame. In some cases, they very well might be, but some of the things attributed to them are probably exaggerations.

Like fake news probably has little to no effect on election outcomes simply because most of it is so outlandish that unless you are a hyper-partisan to begin with, you would just blow it off. And if you are hyper-partisan, it’s red meat, it makes you feel even better.

Like a fake news headline, Obama bans the pledge of allegiance from American schools or Joe Biden calls Republicans the dregs of society. I think most people would, unless they’re already in the right-wing fever swamps, would not believe them. Those even in those fever swamps, I don’t think they really care whether they’re literally true or false, but they’re very happy to read them, they’re, titillated, they’re happy to pass it on. It reinforces their moral condemnation of the other side.

Whether it moves the needle on elections is unlikely because so few people get it as a proportion of all of the social messages. Anyway, that’s just one example of a study, this was by Brendan Nyhan, that actually tried to see whether the effects are as pernicious as we feel. And there, it’s probably not a major phenomenon.

Compared to something else, other forces that certainly do move the needle, especially in the United States, hyper-partisan cable news networks like Fox News. Ingenious studies have shown that they really do make people more conservative. It isn’t just that conservatives flock to Fox News. It’s Fox News makes people more conservative.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Let’s talk about some of the other institutions that you think are having a less than beneficial effect on rational discourse. You write in your book to bring up another quote, universities have a responsibility to secure the credibility of science and scholarship by committing themselves to viewpoint diversity, free inquiry, critical thinking, and active open-mindedness. Talk a little bit to us today about what you think the state of the university is? Why do you believe it’s important to the sustenance of a rational society? And why do you feel in certain cases universities are failing in that mission?

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. So, I mean, certainly what’s coming out of universities in general, is better than what you get on cable news or Twitter, so I don’t want to try to drag down the whole enterprise. And while I’m at it, bite the hand that feeds me. I’ve spent my life in the university, continue to draw a salary from the one with the biggest name brand of all.

But I think not all is well with universities. And indeed there are data that show that universities have become increasingly politically and ideologically narrow. That they’re becoming a left-wing monoculture. The prominent conservatives or even right-of-centre thinkers are often in their eighties and nineties, and due to become emeritus and worse. There is growing, although not completely dominant, intolerance of the idea that people who express unorthodox views should have a platform or a forum.

There are terrifying habits such as journal editors succumbing to pressure from social media to withdraw controversial articles. Not just allow a rebuttal to them, which is what they ought to do, but to remove them from the journals, to throw them down the Orwellian memory hole.

That controversial speakers are shouted down. Again, this is very different from argued against, which they ought to be, but prevented from articulating their positions. And people know it because some of the more ludicrous examples have spilled out from the campus, and are widely circulated. A professor, my friend, Nicholas Christakis, whose wife, Erica Christakis, wrote an oped saying, students should decide what Halloween costumes they wear without being told by adult authorities. And a mob of students cursed and screamed at Professor Christakis at Yale. And the president, instead of sanctioning students for cursing and screaming and mobbing, actually praised them. Now, these videos went viral, and it saps confidence in the university as an institution. Where opinions can be evaluated in terms of their truth value, as opposed to their conformity to some left-wing orthodoxy.

And indeed even, especially in cases where the scientific consensus is pretty clear, such as in human-caused climate change, which I have made the case for in my book, Enlightenment Now. And then people write to me or speak to me and say, well, you say that it’s the scientific consensus, but why should we give that any weight? Because the consensus could just be that anyone who disagrees gets bullied and de-platformed and canceled and sanctioned. If that’s the way universities work, then why should the scientific consensus mean anything to us? And it’s not an illegitimate question. There probably are cases in which there is a consensus. I don’t think climate change is one of them. But there probably are cases where there’s a premature consensus because anyone departing from it will be punished, sanctioned, canceled, de-platformed.

And that means that the entire academic establishment calls itself into disrepute and casts doubt on its own contributions. So, that’s a problem that we in universities really ought to do more to address.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Steven, thank you for that answer. I think it’s just fascinating to think about how these debates reverberate beyond the university campus and the effects that they can have on society as a whole.

Other institutions that you’re concerned about, Steven, courts, we’ve seen increasing charges of politicization around courts. I know in your book, Rationality, the judicial system is one of those places that generally is seen as inculcating a sense of shared rationality and understanding norms.

Maybe you could just provide us with a couple more examples of areas of vulnerability in our society, where reason is under attack.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. So the thing about institutions that do in general on average ideally push towards the truth is that they do have some kind of adversarial process. Where one person, no matter how confident they are, and possibly how deluded they are, they don’t get to impose their view. That other people can criticize them. And so you have these adversarial proceedings in peer review in science and scholarship, in open debate in parliaments, in adversarial proceedings, in the judicial system. So all of them, one person can try to spot and make up for the flaws in another person’s reasoning. That’s what makes these things work.

So whenever those institutions get out of whack, where that’s not what’s happening, that’s when there’s cause for concern. So we’ve talked about academia. I mean, the most obvious example where that’s happened in the judicial system is the American Supreme Court. Where more and more of the decisions simply are predictable based on the political party of the president that appointed the justice.

Partly that’s built into a real flaw in the system, namely lifetime tenure for Supreme Court justices, which is mad. This makes every nomination highly politicized because people know that it’s going to alter the constitution of the court forever.

The process of confirmation of justices, which partly by procedure, partly by the change in norms has become highly politicized. Most obviously when Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, simply held up the replacement for Antonin Scalia when he died, simply by waiting for Obama’s term to expire so that a Republican, rather than a Democrat, could nominate the next justice. Now that is a pathology in the system when that can happen. So that’s the most obvious example. But there are no doubt expert watchers of the judicial system in the United States and Canada may know about other examples.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Steven, I want to now switch gears with you a little bit to try to get practical here and help our viewers think through things that they can do in their lives to be more rational either on an individual basis or in their interactions with other people and institutions.

And maybe one way to ease ourselves into that conversation is to get a sense from you of what are some of the most common reasoning mistakes that you make? I know you explore a bunch in your book. But I wonder, having done all that research, having taught students about this now extensively, what’s the big mistake that we all make? Because I want to then get your advice on how we correct for that when it comes to our own capacity to reason.

STEVEN PINKER: So, you’re not asking necessarily about me personally, but about all of us?

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Yeah. Just your observations of human behavior. And maybe what studies show. But maybe also what you see in your day-to-day life.

STEVEN PINKER: Well, certainly a big one is to fall victim to the availability bias. That’s the type of name given to that cognitive quirk by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, by which we judge prevalence, probability, danger, risk, according to examples that come to mind, that are available in memory. We use our brain search engine as a way of doing probability. So, is car travel dangerous? Well, my great aunt lost her life in a car crash. So, yeah, it is. Or a plane crash. Or COVID. Or the flu. Or living in a polluted city. Where we have the great benefit of having data available to us on all of these questions, but still what we think of is, did it happen to my uncle? Or did it happen to me? Can I remember it?

So, that’s a big one. Probably another one is expected utility or the theory of rational choice, that is do we weigh… In having options, do we weigh the probability times the cost or benefit in choosing outcomes? A simple example is buying an extended warranty for an appliance, which a lot of people do. Often 25% of the price of the product. Unless the product fails… One out of every four products fails, that’s a losing bargain. More consequentially, do we do it within our own lives when we step on the gas pedal to get home 17 seconds faster with an increased probability of losing our lives or killing someone else? If you thought it through in that way, you’d think, yeah, if I’m late by a few seconds, it’s really a price worth paying compared to the gamble that I would take with my life. But probably people don’t think that way thoroughly enough.

That’s a couple of examples. And more generally, I think doubting our own wisdom, knowledge, competence, another very pervasive bias is called the bias bias. Namely, all of us think that everyone else is biased, but not ourselves. And just thinking twice, thinking, gee, how good really is my track record? Do I make mistakes? Should I take advice from other people? Instead of kind of trusting my gut. Should I look at the base rate of other people making that same decision in my shoes? That is another common error of reasoning. We trust our own intuition too much.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: And in the course of this pandemic, Steven, you must have seen all kinds of examples, as someone who’s constantly thinking about what behavior is rational or not, what action on the part of government is rational or not have, have we failed the test of reason in the last 20 months?

STEVEN PINKER: Oh, yes. Well, certainly, most obviously, in the case of the various politicized conspiracy theories we had in the United States. Donald Trump saying, “It’ll go away, it’ll be a miracle. You just wait a couple of weeks and it’ll be gone.” Wrong. We have most saliently, since then, people avoiding vaccines, for which the evidence is overwhelming that they are safe and effective. But there are intuitions that people have that injecting a version of the disease agent into your flesh can’t possibly be helpful. It does go against our intuitions. That’s a nice case where our intuitions are wrong. Vaccination is, perhaps, the smartest thing that our species has ever invented, including the COVID vaccines. On the other hand, I think there have also been failures from the public health authorities, the politicians, the scientists. Partly because of politicization early on. Every single issue, when it came to COVID treatment, became a left-wing versus a right-wing issue.

And sometimes I think, more often than not, the left was aligned with the better position, but not always. Such as the utter dismissal of the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab in China. The Wuhan Institute of Virology. That was considered to be a racist, right-wing conspiracy theory. It might be mistaken, but we don’t know. And we really should know, and it is a live possibility. I’ve bet against it publicly. I have skin in the game that it was zoonotic, but it’s a terrible mistake to just squash a plausible alternative explanation because it reminds you of your political adversaries. And also in that vein, even when it’s not politicized, I think there’s a mistake when public health authorities act like a priesthood, like oracles. We’re the scientists, do as we say, as opposed to showing their work to saying, look, our starting position about everything is ignorance. We don’t have access to an oracle. We’re not divinely inspired. Everything that we do is based on gathering data. Here are the data that we have so far that lead us to recommend this as a policy.

Protecting them when facts change and advice changes, as it did during the pandemic, as it is, if they sound like priests to begin with, as soon as they say something wrong, they just get dismissed. Whereas at every step, justifying advice, respecting the intelligence of the population a bit more, I think, would’ve been more effective at conveying best practices at every step.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Those are great insights. Well, Steven, what are the mental habits? How would you recommend that we go about kind of exercising that muscle of rationality? Is there a series of techniques or a discipline? I mean, I’d urge everybody to, obviously, pick up your book, Rationality, because I really enjoyed how practical it is. And you’re practical right off the get-go through the first half of the book or more. But what if you could just give us some clues here, at least stimulate us to think, to take the next step, that we can train ourselves to push back against some that these biases and inclinations we have towards irrationality so we’re not just subject to the fates here.

STEVEN PINKER: And certainly one of them is simply to think twice. That is, don’t trust your first impulse. Sometimes it’s right, but you should step back and give second thoughts because we know that a lot of errors and fallacies come from a gut-level thinking. Another is to cultivate the mindset, that’s sometimes called active open-mindedness, and that is that you always should be prepared to calibrate your degree of belief in something according to evidence as it comes in. Not to tie up your own ego or your own moral worth with your factual beliefs. But to realize, look, we’re all ignorant of everything, pretty much. We try to increase our confidence in a particular belief, according to the strength of the evidence, according to its consistency with our understanding of how the world works. But often we should be prepared to be surprised and challenged. So, that’s the general mindset called active open-mindedness. There’s a quote attributed to John Maynard Keynes when he changed his mind and someone called him a flip-flopper, or words to that effect. And he said, “Well when the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” Great story. He probably didn’t say it, but someone said it, and it is worth keep keeping in mind.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: You make an important distinction between logic and reason. I think it’d be interesting for people to hear that played out a bit by… Just unpack that for us because I think when we think about training ourselves in these habits, you are arguing it’s not just logic. It’s a capacity and an ability to reason that is distinct and different from logic on its own.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. Now, admittedly, sometimes the word logic is used as a synonym for rationality, as in Mr. Spock said, I don’t like working with humans, their illogic drives me crazy. But technically logic is the set of rules that allow you to deduce true implications from true premises. Now, it only works to the extent that you are sure that your premises are true in the first place, which we rarely are. And where the rule of inference, the P implies Q, if P then Q, if we know that that always applies. In a lot of cases, our knowledge just falls short of that. We have a degree of confidence or credence in a belief, say, from zero… On a scale from zero to one. And as evidence comes in, we increment or decrement our degree of confidence, but it’s never one or zero, true or false.

Also in many cases, there isn’t just one fact that is completely dispositive, completely certain, that just settles the issue once and for all. There are lots of considerations, each one of which kind of… Some increase your confidence, some decrease your confidence, and you kind of weigh them all. I think a lot of that kind of probabilistic reasoning is what we think of as intuition or… And that is, in part, what powers current artificial intelligence models, the so-called neural networks or deep-learning networks. They don’t do step-by-step deduction like in a traditional computer program, but they weigh together thousands, sometimes millions, of bits of information, little cues, each one of which kind of increments or decrements confidence in a particular hypothesis. So, that’s why logic… There aren’t that many things that you can just settle once and for all with a logical deduction. Often you’ve got to weigh a lot of evidence.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Yeah. You mentioning computers stimulated me to think, having read your book and some of your writing on this, that are you optimistic that, as we have more sophisticated machine learning, even as we approach some form of artificial intelligence in machines, does this help us? Does this become a way out of our illogical inclinations? Is it really in our interest to give moreover to these machines? I know that would be counterintuitive, possibly abhorrent to many of our viewers, but it seems like they’re actually pretty good at this and they’re getting better at reasoning.

STEVEN PINKER: I think that there probably are benefits to be gained in, not necessarily turning over the decision to an artificial intelligence system. Because ultimately, we’ve got to decide that. So, it’s the responsibility of the person who… Even outsourcing the decision to something else. That’s a decision. So, we’ve got to always think carefully about, ultimately, what the decision is. But I think more of our decisions could be and should be informed by artificial intelligence. Just an extension of something that psychologists have known for decades, which is that even… Forget fancy schmancy, deep-learning networks. Even with a simple statistical formula, you have a bunch of predictors, you add them up. If they’re above a level, you make one diagnosis, below it you make another one. That, more often than not, outperforms the human expert. That human expertise, we tend to overrate it. Because even though we are pretty good at identifying particular kinds of evidence or information. Is that person trustworthy? Is that person competent? We’re not good at combining them.

Just like if you have a whole bunch of groceries on the supermarket checkout counter, you can’t say to the checkout person, well, it looks to me like it’s about $77. Is that good enough? They’ll say, no, no, I’m sorry. It may look that way to you, but you have to count. And that’s probably true for a lot of human decisions. And I think we overestimate ourselves and probably, in the future, a physician plugging the symptoms and the base rates into a formula, an artificial intelligence program would probably do better than relying on their experience, on their of similar cases. And likewise in business, likewise in other areas. And again, we always have to justify our choice of an algorithm in informing the decision. And ultimately the human is in the loop if only for choosing one algorithm over another and having to defend that choice. But when we ask how biased, how inaccurate algorithms are, we should always compare it to how biased and how accurate are humans. And the answer is more biased than we like to think.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Fascinating stuff in our remaining moments, let’s talk a little bit more about solutions because you think there are some practical things, not simply at the individual level that we can do to be more rational, but society can take a role. Education. How institutions themselves work and function. Explain a bit of your thinking there to us.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. I do think that the models of rationality, like probability, like logic, like correlation and causation, like rational choice, should be woven into our curriculum.

Rational choice should be woven into our educational curricula earlier on. I think a lot of what we teach kids goes back to the middle ages, to the monks and priests, and ought to be rethought. There are only so many hours in a day, admittedly, so that if you introduce a base rule, which I think everyone should know, something’s got to give, but those are discussions we ought to have. What should an educated person command? And I think many of the tools of rationality, including hygiene for critical thinking. You attack the argument, not the person. You don’t invest too much faith in authority and prestige, but rather in the quality of argumentation. Those mental habits ought to be inculcated early on and should be second nature in our public discourse, openness to evidence, active open-mindedness, and so on.

I do think that the particular tools, like the ones I try to explain in rationality, should be second nature to people, but more generally, our general norms and mores of discourse should have more open-mindedness, instead of just immediately reaching for the right-wing position or the left-wing position and just hammering it home, and whenever a bit of contrary evidence comes in, racking your brains on how to make it go away, how to refute it, consider “Well, maybe I should adjust it. Maybe I should give this a second look.” That set of habits, it’s part of the norms and mores of this nerdish community called the Rationality Community to try to flaunt their openness to evidence, their rational thinking, but they should be part of everyone’s norms. And it is bracing sometimes to read, say, an essay from a proponent of the rationality community, like the blogger Scott Alexander, where he’ll give an argument for something he said. “Well, but maybe I’m wrong. Here are some of the reasons that I take seriously as to why everything that I just said might be mistaken.” And it’s surprising when you can compare it to a typical op-ed, which just hammers home the point moreover, furthermore, and in addition. We should get more in the habit of saying, “Yes, but on the other hand, but this is what could prove me wrong.”

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: So to play that back to you, Steven, is there a counterargument to your argument that maybe you don’t give credence to, but you’re willing to think or it’s something you want to explore more? What of your detractors’ key points… Which, if any, resonates with you?

STEVEN PINKER: Well, I’ve said a lot of stuff, so it would depend on which particular claim.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Well, let’s talk about rationality and your views here about the ability for people to learn these habits, for society to reform itself, for rationality to become more prevalent, as opposed to less. I mean, it connects back into some of your thinking that many of our viewers will be familiar with around progress.

STEVEN PINKER: Yeah. So when it comes to rationality, there can be the cynical view that we are cavemen, that it’s hopeless to try to collectively strive for rationality, that really what we ought to do is promote the side of justice and correctness, which often means one’s own side. And one could, I argue, say the left-right disputes that it is not symmetrical that, in fact, that the distortions that are more flagrant and severe by the right, and the only reason that universities have become more left is that they… As some people put it, reality has a liberal bias.

There’s the criticism that attempts at fostering objectivity, truth, and rationality are… Since there’s no such thing as objectivity and truth, they’re inevitably going to be ploys by the powerful to cement their own privilege, often, in particular, the power and privilege of white heterosexual males. That encouraging the expression of opinions that will disadvantage vulnerable people, the harm that people could undergo outweighs any commitment to free speech or open inquiry as a general principle. Those are some of the counterarguments. I’ll have to say, and perhaps I’m biased in saying this, but when it comes to rationality, as opposed to some of the other positions that I have argued, such as the risk of war has gone down, where there can be debates, depending on the interpretation of history and interpretation of trends.

When it comes to rationality, it actually is very hard to mount a contrary position because the only way you can do it is by appealing to rationality itself. And so rationality is special in that, even though, I must be willing to confess to flaws and uncertainties in my arguments for anything else. If you do that for rationality, the question is, is that opinion itself rational? And if not, should it be taken seriously? So I’d say that, of all of the things that I have advocated for, I think rationality is special and there, I’m less willing to entertain counterarguments because if the counterargument is any good, it would have to be rational

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Just to touch on one of those counterarguments, because it’s a big part of the popular debate right now, especially on university campuses, and this is this idea, again, of power relations and that existing structures have certain ways of constructing reality around norms that privilege their position and lead to the continued subjugation of traditionally oppressed groups. So just on that particular one, I’d like to hear your refutation of why we shouldn’t lump rationality, the rules of reasoning, into maybe, in some cases, a legitimate condemnation of invested power structures in our society.

STEVEN PINKER: Well, there absolutely should be criticism of unjustified power structures and of structures of oppression, institutions and norms and rules and biases that disadvantage people. But to make that case, that can’t go against rationality because if itself it is rational, then its actual power comes from that very fact. And so one absolutely ought to question, subvert the imposition of beliefs by brute force, by power. That is the application of rationality. It’s not contrary to it. Now, some people make claims to be rational in imposing dogma or privilege or advantage, but they’re mistaken. And it is rationality that allows you to point that out.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Yeah. Just I’ll bring up another quote word from your book, Rationality. You wrote, “My greatest surprise in making sense of moral progress is how many times in history the first domino was a reasoned argument.” You obviously give the example of slavery in that case.

STEVEN PINKER: Well, indeed, and I end the book with an argument that, far from being opposed to social justice and moral progress, it’s rationality that propels it. Not only historically is it the case that great movements for social change, such as abolitionism, had rational arguments to appeal to… And when it comes to abolition, none was better than Frederick Douglass, himself a formally enslaved person, but that they really should. Unless there is a good reason to change some practice, to question some law or custom, unless you can justify that, that isn’t social change you should endorse. It may just be breaking things. It may just be a lynch mob or a pogrom or lead to the situation getting worse rather than better. Rationality also always has to be the lodestar by which we choose some activist movements to support, namely they will rectify injustice. They will make people better off if implemented. And, in fact, I give examples for women’s rights, for democracy, for peace, for religious toleration, where centuries ago people did do the work of making the argument, and it’s a good thing that they did. And they were right.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Yeah. Steven, just finally, your 12th book now, decades-long career, a commitment here to these ideas that you’ve stuck with. And I’m just curious of what’s been the motivation behind all this for you, personally? Where does this wellspring of concern about reason, rationality, its role in human progress, how we should think of ourselves as a species, how we should claim our agency?

STEVEN PINKER: Well, personally, a lot of it has just been driven by the curiosity about what makes us tick. People say, “Why did you choose to… Why did you go into psychology?” And I say, “Well, what could be more interesting than how the mind works?” Now, admittedly, that’s a bit of a… There’s a bit of circularity in there. I find it interesting. Perhaps not everyone finds it as interesting as I do, but I do have a drive to figure out what is this strange thing that we call human nature. But also, it’s not just curiosity. I like to quote Anton Chekhov, “Man will be better when you show him what he is like.” Today, we would say humanity will be better when you show them or it what it is like. I do think that a deeper knowledge of what makes us tick makes us better equipped to dealing with our problems, to coming up with democratic, equitable, and progress-promoting solutions.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Well, Steven, thank you so much for your scholarship and your generous time today I hope that this awful pandemic can finally be over and we can have the pleasure of hosting you again in Toronto for either a discussion like this or another debate. I’ve really enjoyed the time that we spent together today.

STEVEN PINKER: Me, too. I sure hope so, and I thank you again, Rudyard.

Recommended for You

Fred DeLorey: Why real Christmas trees matter more than ever

Ray Pennings: A good Christmas reminder for Canada’s leaders: Religion is a public good

Sean Speer: Canada needs to kickstart its cultural policy

Eric Lombardi: Dare to be great: Ten radical ideas to restore Canada’s promise in 2025