Much Canadian analysis and commentary tends to focus on the fault lines in our society. It seems inherent to the cobbled together nature of the Confederation project that we concern ourselves with these potential fissures and how they may manifest themselves in our economy, culture, and politics.

The historic divide between English and French (the “two solitudes” as it was famously called) is certainly the best known and most closely studied in Canada’s history. Recently there’s been growing interest in the urban-rural divide and its broader political economy implications. Progressives similarly tend to focus on issues of class or race or gender and the potential for systemic discrimination.

This hyper-focus on potential fissures in Canadian society derives from legitimate concerns about basic political stability. It’s a sort of prudential hedge that aims to ensure that no particular fault lines grow so large that our sense of fairness is offended or Canada’s social cohesion is threatened.

COVID-19 has shone a light on an underexplored fault line within the country: the growing government bureaucracy and those who must pay for it.

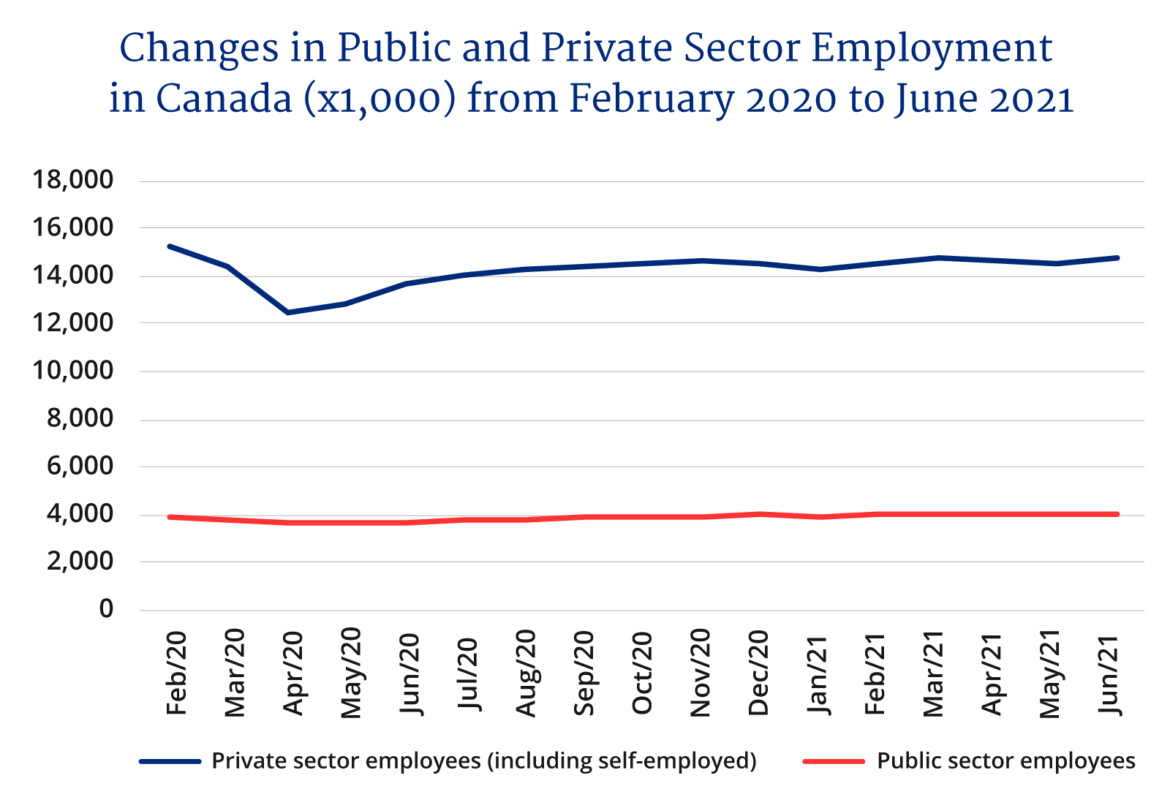

This divide is illustrated by Statistics Canada’s latest jobs report. The private sector, including those who are self-employed, has shed 520,400 net jobs since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, while the number of public sector jobs across the country has increased by 180,000.

Although some of these public sector jobs may be a temporary spike in response to COVID-19, it’s worth recognizing that more than 50,000 are classified as “public administration.” This means that a significant share of these new hires isn’t necessarily on the front lines of the pandemic response, including, for instance, vaccine distribution.

This expansion of the government’s payroll (particularly for non-COVID related work) in the middle of the pandemic seems to fail a basic fairness test. There’s something inherently unfair to add to the long-term tax burden of businesses and households that have already been saddled with government-mandated shutdowns, pay cuts, and job losses.

It risks exacerbating the nascent divide between what Globe and Mail columnist John Ibbitson has described as “the public class, who live on the avails of taxation, and the private class, who pay the taxes.”

As he explains:

“The public class includes the school teacher, transit worker, public servant, nurse, student, artist, social worker, first responder, city worker and the like. Most of them would welcome a further expansion of the state, which would benefit their class.

The private class includes the store clerk, store owner, accountant, factory worker, office manager, salesperson, truck driver, marketer, oil worker and others trying to hang on to their job and as much of their money as possible.”

These types of formulations can risk succumbing to oversimplification. Public sector workers do of course pay taxes too and millions of private sector workers benefit from various public programs such as the Canada Child Benefit, Canada Workers Benefit, and so forth. The dividing line between so-called “makers” and “takers” may not be as clear as it’s sometimes characterized.

But as a basis for understanding Canada’s modern political economy, Ibbitson’s formulation has merit — particularly as the nature of private sector employment evolves from the traditional industrial model to less secure forms of service-based work. These secular trends suggest that the work experiences of public and private sector workers in Canada are bound to continue growing further apart.

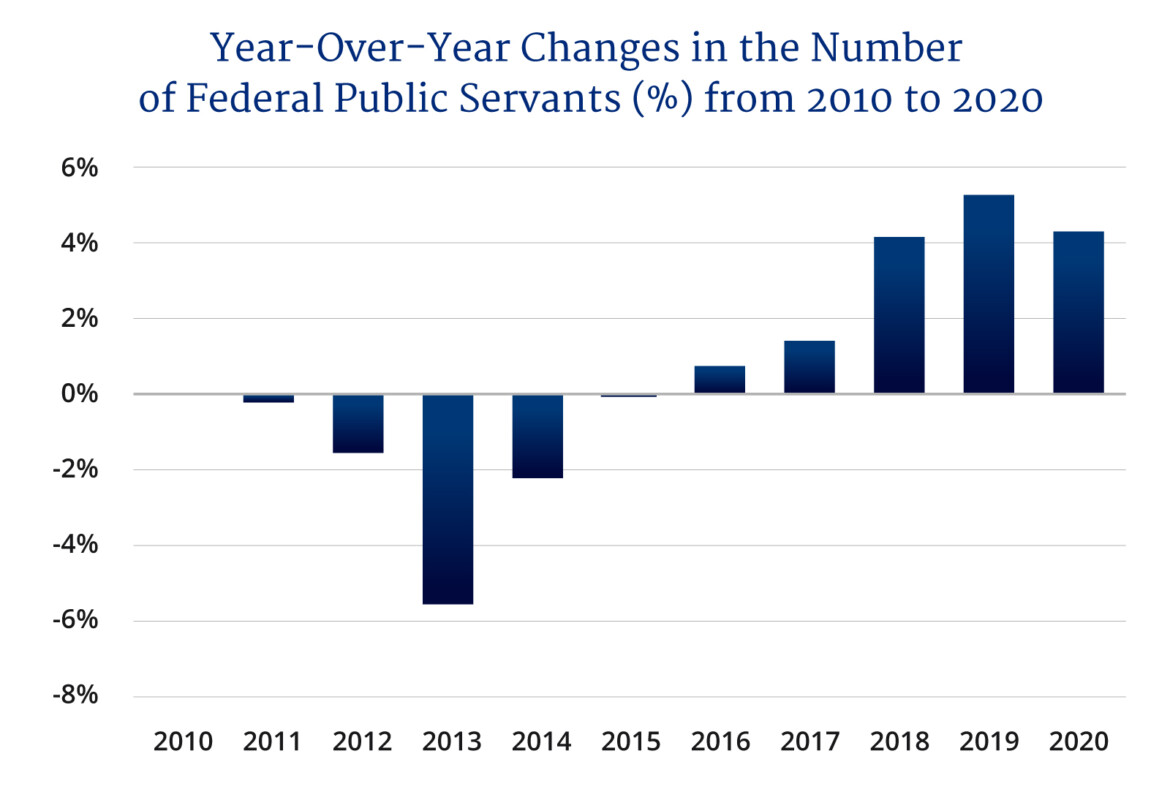

This divide was already notable prior to the pandemic. Take one example: After falling by 7.6 percent between 2011 and 2015, the number of federal public servants increased by 16 percent between 2016 and 2020 (see figure). Private sector employment (including self-employed workers), by contrast, grew by just 1.9 percent over the same period.

It’s not just differences in hiring rates either. Research by the Fraser Institute (and others) consistently finds a wage premium for public sector workers in Canada. Even after controlling for factors like gender, age, marital status and education level, Fraser Institute scholars estimated a 9.4 percent wage premium, on average, for public sector workers over their private sector counterparts in 2018. Adjusting for the relative levels of unionization still produces a wage differential of about 6 percent.

Yet this doesn’t even tell the full story. The overall compensation gap is far greater when one accounts for non-wage benefits such as pension and health benefits, job security, and typical retirement age. Just consider, for instance, that 87.7 percent of public sector workers are covered by registered pension plans, compared to just 22.5 percent of private sector workers.

This kind of growing divide in the work experiences of public and private sector employees in Canada is something that policymakers ought to be more cognizant of. It’s the sort of thing that will become even deeper in the future as government spending becomes more unsustainable and the private economy is further held back by labour shortages. We could end up with a two-tier economy: one in which public sector workers earn more, have better benefits and are granted greater job security and another in which private sector workers face more precarious work with fewer benefits and less security.

Under such a scenario, one can envision the makings of a future breaking point: a moment in which the Ibbitson’s private class (which is still represents two-thirds of overall employment) starts to assume a shared identity and in turn supports a political agenda that targets its real and perceived inequities relative to the public class.

That would be an unhealthy political future. It could contribute to a climate of “class warfare” and reinforce a zero-sum politics among different types of Canadian workers. The fault line would run through households, families, and communities. It’s a future that we should seek to avoid.

A better future is one in which the divide between public and private sector workers is narrowed over time through a combination of sensible public restraint and a more productive private economy. This is a key point: progress will require action on both sides of the public and private equation.

Governments will need to limit the growth of total public sector compensation — including wage and non-wage aspects. If public sector workers prefer more non-wage benefits, that should be reflected in slower wage growth. If they prefer high wages, that should involve adjustments to non-wage benefits. The key point though is that there must be an overall goal to minimize the total compensation gap between public and private sector workers.

As for private sector workers, the focus must be on enhancing labour productivity. That’s the best way to raise wages and living standards and the evidence tells us there’s certainly room for improvement here.

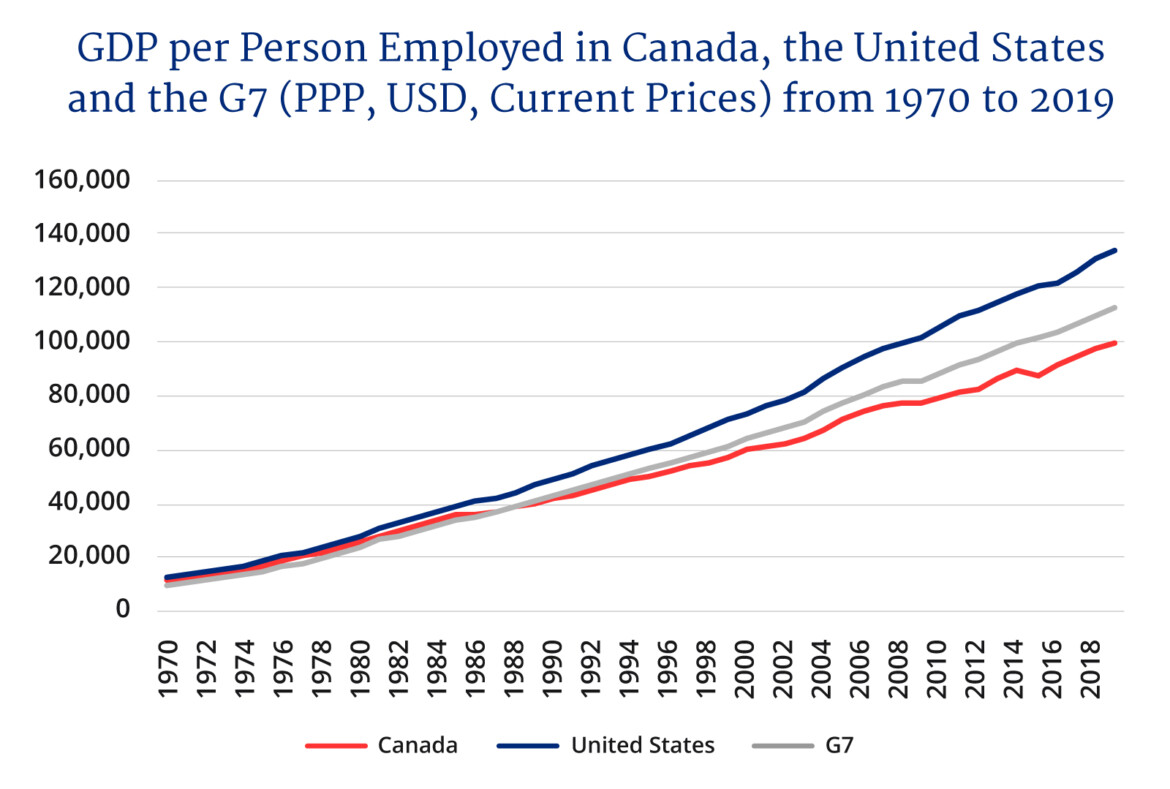

As others have highlighted, Canada’s productivity performance over the past 50 years has lagged its peer jurisdictions. Consider, for instance, that in 1970, Canada’s GDP per person employed was $11,678, which was only $1,276 less than in the United States and $1,830 more than the G-7 average. But fast forward to 2019 and Canada’s GDP per person employed was $34,631 less than in the United States and $12,971 less than the G-7 average (see Figure).

Boosting productivity through investments in innovation and technology must therefore be a top priority for policymakers in the post-pandemic era. It will not only contribute to stronger wage growth for private sector workers, but it will also help the economy to cope with demographic-induced labour shortages, which as the pandemic subsides, will invariably act as a brake on long-term growth.

The upshot: Canadian policymakers need to concern themselves with the growing fault line between public and private sector workers. A renewed commitment to sensible public spending restraint and higher rates of productivity in the private economy can help reshape the policy discussion from one of zero-sum scarcity to one of positive-sum abundance.

That’s the best path to stability, cohesion, and higher living standards for all Canadians.

Recommended for You

Letter to a minister: Canada’s long-term prosperity depends on maximizing our resource potential

The Week in Polling: Liberals and Conservatives neck and neck; American trust in mainstream media hits all-time low; Canadians overwhelmingly reject becoming Americans

‘We’re careening towards a moment of truth’: The Roundtable on the state of the economy and the perils of pipeline politics

‘It’s an incredibly precarious moment for the prime minister’: Hub Politics on Carney’s charm offensive in Washington

Comments (0)