According to Statistics Canada, January saw annualized Canadian inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index surpass 5 percent for the first time since September 1991, clocking in at 5.1 percent. Within this increase are masked several separate components whose impacts on daily life depend on whether they are a major component of your consumer basket.

For example, shelter costs rose 6.2 percent whereas mortgage costs fell 6.8 percent. Fresh or frozen beef was up 13 percent and gasoline was up nearly 32 percent. Indeed, for those so inclined, Statistics Canada has thoughtfully even provided the ability for Canadians to calculate their own personal rate of inflation with a web-based calculator that allows you to break out your monthly expenses and see how you are doing.

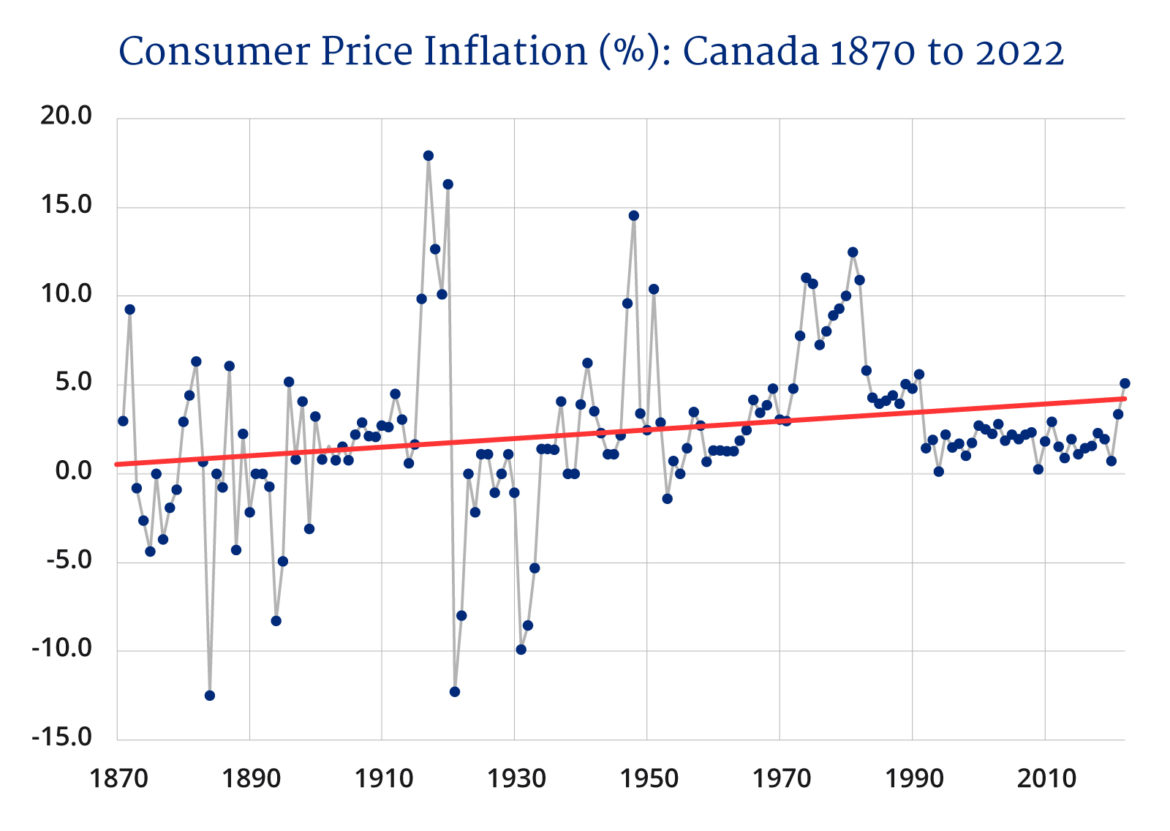

The angst and attention over rising inflation have focused on whether it is transitory, and now more recently over the steepness of the current rise based on the economic history of the last thirty years. A longer view of Canada’s inflationary trends suggests that, while the current inflationary surge represents a marked divergence from the trends of the last few decades, when looked at over a longer time horizon we are in neither the best nor the worst of inflationary times.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The accompanying figure provides a snapshot of consumer inflation over the long haul—annual consumer inflation from 1870 to 2022. The period from 1870 to 1913 is data from the international Jorda-Schularick-Taylor Macro History Database. The period from 1914 to the present is from our very own Statistics Canada Consumer Price Index. As the chart illustrates, the current surge of 5.1 percent to date in 2022 is indeed the highest in nearly 30 years, and yet a glance further back shows that there have been other times when things have been much worse. What is also of interest is that the long-term linear trend of inflation is not flat like real per capita GDP growth but actually slightly upward sloping, suggesting a bias towards inflation in modern economies.

Those of us of a certain vintage can still remember the inflationary surge of the 1970s and 1980s which were also accompanied by rising unemployment and economic stagnation. Hence the term “stagflation”. The gradually rising inflation of the late 1960s and early 1970s resulting from a spending boom and looser monetary policy was given a steroid-induced push from the oil price shock brought about by OPEC in 1973.

Inflation surged as expectations of rising prices became ingrained into labour negotiating behaviour, and this inflation was ultimately tamed by the tightening of monetary policy—an increase in interest rates—in the early 1980s and repeated in the early 1990s. Whether inflationary expectations will again take off at present is unlikely given that during the late 1970s Canada’s rate of unionization was just under 40 percent whereas today it is closer to 25 percent, with much of that in public sector unions subject to government salary restraint legislation at present.

Going even further back, inflationary surges appear to be largely associated with wartime conditions of shortages and hardship, whether they be the First or Second World War era. The First World War was a period of economic crisis with the wartime production demands resulting in scarce labour, rising interest rates, and shortages of consumer goods that persisted into the years immediately after the war. While inflation was low in 1914 and 1915, it soared to 10 percent in 1916 and peaked at 18 percent in 1917 before diminishing to 10 percent by 1919.

However, in the post-World War I era, inflation was only tamed after the major recession of 1921 which saw deflation of over 10 percent. While World War II also saw inflationary pressures, the lessons of the first had been learned and inflation was kept under control by government price control policy. Nonetheless, war inflation managed to peak at about 6 percent in 1941 before declining.

Prior to the creation of the Bank of Canada and monetary policy, taming inflation and indeed price deflation was often the result of market forces in the wake of major economic downturns. Again, as the chart illustrates, there were major deflationary periods in the 1870s, the 1890s, the early 1920s, and then the 1930s. These were all major economic contractions. Indeed, the 1870s used to be known as a great depression experience until the great depression and property price collapse of the early 1890s which assumed that mantle until that of the 1930s occurred.

Large-scale price deflation has characterized consumer prices only on occasions prior to the onset of modern fiscal and monetary management by governments—a post-World War II policy development. The more freewheeling world of the late 19th and early 20th was accompanied by greater variation in economic indicators as demand and supply operated relatively unhindered to generate larger fluctuations in prices and incomes. When it comes to inflation, our current economic woes are relatively tame compared to days of yore and hopefully will remain so.

Recommended for You

Need to Know: Buckle up, we’re in for a wild ride in 2025

Theo Argitis: From a Trump shock to trade shifts to climate realities, here is what will shape Canada’s 2025 economic playbook

Eric Lombardi: Dare to be great: Ten radical ideas to restore Canada’s promise in 2025

Ignore the political fireworks in Ottawa, the real story is Canada’s deteriorating fiscal situation: BMO