In a recent Hub Roundtable podcast episode, Rudyard Griffiths raised concerns about the Bank of England’s £65bn infusion of capital into the economy in a context where inflation is already sitting around 10 percent. While his concerns were well-justified, they don’t fully cover the consequences of the extraordinary fiscal and monetary policy action that we’ve seen in recent years.

Quantitative easing and other such measures have come to obscure the true costs and consequences of our collective choices. Put differently: they’ve prevented us from being able to distinguish between good and bad policymaking.

When the Truss government unveiled a plan for £45bn in unfunded tax cuts alongside an energy price cap that will likely send their government well over a 100 percent debt-to-GDP ratio, chaos hit the bond markets. Was this a good policy? A bad policy? How will we know? The BoE has jumped in to keep the financial waves at bay.

This makes it virtually impossible for British voters—who are the ones ultimately responsible for holding government accountable—to assess the true benefits and costs of the government’s policy choices. They are simply along for the ride.

The bill always comes due, and the Truss government should soon learn that you cannot have your cake and eat it too. Or will they?

In order to prevent an “unwarranted tightening of financing conditions and a reduction of the flow of credit to the real economy,” the BoE’s Financial Policy Committee said it would purchase gilts on “whatever scale is necessary” for a limited time. This extraordinary action effectively breaks the feedback loop between the government’s policy choices and their full consequences.

What will happen when the BoE raises interest rates to 4 percent or higher in the winter? There are 1.8 million ARM mortgages (the equivalent of the variable mortgage) in the U.K. These households would experience a spike in their borrowing costs. While many are predicting this dose of tough medicine, this recent case might be cause for doubt. On a recent episode of The All-In podcast, Sri Lankan billionaire Chamath Palihapitiya argued that instead, we are likely to see more of the same. When the going gets tough, the central bank will simply inject more money into the economy. The BoE did it just a few weeks ago. Who is to say it won’t do it again?

In other countries around the world, the same thing seems to be playing out at different speeds. The U.S. Federal Reserve currently has rates at 3.25 percent and is expected to raise them up to 4.5 percent before the end of 2022. It’s the only central bank left standing—the only central bank who, as Griffiths says, hasn’t blinked—when it comes to finally recognizing the negative effects of its loose money experiment and taking action to restore price stability.

Yet while we won’t see tens of billions of dollars injected overnight as we did with the BoE, it’s still not clear that the Federal Reserve will be able to hold the line through 2023—especially as some prominent voices are already calling for it to (at the risk of mixing metaphors) take its foot off the proverbial gas. If the last few years have taught us anything, we can expect to see more of the same, just strung out over a longer period.

In Canada, we’ve not been immune to these issues. The pandemic saw the Bank of Canada deploy quantitative easing in the name of macroeconomic stability. It was part of a broader mix of extraordinary fiscal and monetary policy choices that involved record annual deficits and huge sums injected into the economy.

Were these good policies or bad policies? How do we know what score to give? It is obvious by now that those hit the hardest during the pandemic were the least well off—though evidence also shows that this group’s household income actually went up due to government transfers. As governments survey the pandemic’s damage and the need for reform (including to Employment Insurance, health care, and so on), there’s a big risk that they’ve come to be socialized in a solution bias that simply favours throwing money at our problems.

Let’s pretend the BoE didn’t recently try to calm the markets. Defined benefit pension plans, including popular workforce pensions in the U.K., could have fallen into insolvency. With an aging population, the U.K. might have experienced serious political turmoil. Prime Minister Truss may have even been booted from office less than a month after she started. (At the time of writing, she is still in power though, notwithstanding these extraordinary market interventions, her grip on power seems tenuous.)

The damage caused to pensions would have been horrible. That cannot be overstated. But it also would have exposed the true costs of the government’s policy choices to the public. It would have permitted the feedback loop between actions and consequences that is fundamental to our democratic system.

Beyond further currency devaluation for the world’s most services-export-intensive economy, these costs for democratic accountability shouldn’t be ignored. The cumulative effect is to effectively blur the public’s sightline into the benefits and costs of government policy.

The Truss government has since walked back its plans to cut the U.K. tax rate for top earners and has scrapped almost all of the ”mini-budget”, so the public will have to wait for the next opportunity to score their newest government’s policymaking. But it won’t be easy. It is hard to see the full policy picture clearly when you’re wearing the goggles that come with extraordinary fiscal and monetary policy.

We must be willing to remove these goggles and be prepared to see something we don’t want to see. Honest resilience comes from honest leadership through hard times.

Recommended for You

The U.S. is out-competing Canada in rewarding top-tier immigrants with higher pay: Study

The Weekly Wrap: Stop painting Alberta as the villain of Canada

The Week in Polling: Majority of Canadians want the Alberta-B.C. pipeline; Optimism about the Carney government drops; 87 percent of Canadians concerned about the state of housing

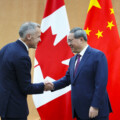

‘An approach that lacks principles’: The Roundtable on Canada’s confusing China reset and the lack of scrutiny on Carney