One of the core pieces of Ottawa’s approach to tech and cultural policy is the Online Streaming Act, or Bill C-11. The bill, which represents the first change to the Broadcasting Act since 1991, requires broadcasters and streaming platforms to do the following: showcase Canadian stories and music, contribute to the production of Canadian stories and music, and support a broadcasting system that reflects Canada’s diversity.

According to Ottawa, the act is necessary to “give Canadians more opportunities to see themselves in what they watch and hear, under a new framework that better reflects our country today.”

For Canadian content, the Trudeau government is hell-bent on applying outdated regulations to innovative tech platforms like Netflix, Spotify, and YouTube. These platforms are successful because they provide consumers with what they want in terms of video and audio content. It seems quite paternalistic for the government to interfere and require that these companies produce Canadian content, regardless of whether there is consumer demand for it.

This is problematic because Canadian content regulations tell consumers that they want, or should want, to consume Canadian content, and then force companies to create or promote content based on that misguided assumption.

I, of course, want Canadian artists and content creators to do well and thrive, but I also know that the Canadian media/entertainment space is mature enough to stand on its own two feet. It would be better for Canadian success to be a result of meeting consumer demands and not the result of a government decree.

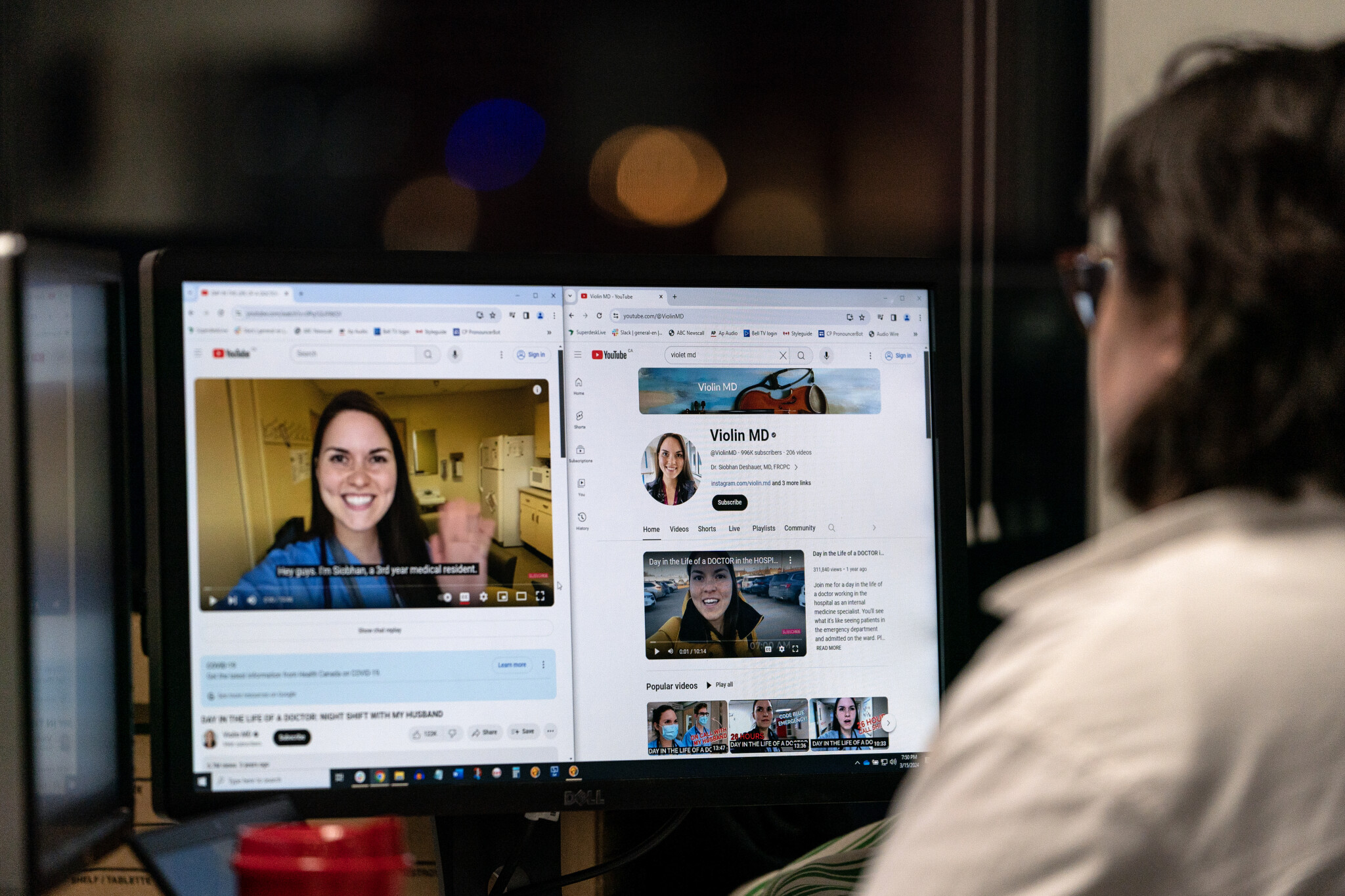

And the ability to stand on one’s own two feet has never been easier than it is today, largely because these alternative platforms, especially Spotify and YouTube, have almost no barrier to entry. If someone has talent, let’s say as a musician, the barriers to putting their content on these platforms are near zero, with the exception of the technical know-how to upload an MP3 or MP4. In fact, one of the most popular music talents in the world, Canadian Justin Bieber, got his start by doing exactly that; uploading videos to YouTube.

Contrast that with how the music industry used to work for Canadians. Shania Twain, for example, had to be found by a talent agent, produce demos, and sign with a record company in order to have her music play on the radio. Much of that process can now be sidestepped because of platforms like YouTube and Spotify.

This begs the question of why Ottawa would want to intervene in an ecosystem that’s worked without their meddling and try to apply Shania Twain-era regulations to an industry that has long moved on.

Supporters of CanCon regulations say these regulations are required to “protect Canadian culture and the people who produce it,” but who exactly are we protecting Canadian culture and its producers from?

If Canadian content isn’t successful in the domestic market, that is because it isn’t appealing to the demands and wants of Canadian consumers. It is backward for the government to meddle to try and shield Canadian creators from the wants of domestic consumers. If legislators want to actually listen to the demands of Canadian consumers, they’d know that Canadians liked these platforms just how they were, and that intervention wasn’t needed.

Plus, we already have a taxpayer-funded outlet to protect Canadian culture and its creators: the CBC. Is the $1 billion the CBC receives not enough to provide a home for Canadian content? Do we really need to be forced to pay for Canadian content as both taxpayers and in the private sector? I don’t think so.

And, despite the intervention from Ottawa, there is no guarantee that Canadian consumers actually engage with the content that is mandated to be available. The availability of content by no means that Canadians are actually going to watch, or listen to, the content Ottawa thinks they should.

And worse yet, Ottawa admits this, on their own website for the act. The act is framed by Ottawa by saying “The Online Streaming Act is about more choice. What you watch and listen to will always be up to you.” That last sentence really should be the end of the discussion. They know that at the end of the day you are going to consume what you want, regardless of the mandates from Ottawa. So why bother in the first place?

Why are we going down this route of inflating costs for these platforms, which are undoubtedly going to be passed on to consumers, to mandate Canadian content that most Canadians just don’t care for?

As Michael Geist, Canada’s Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law points out, the “implementation of the bill has been a regulatory mess, marked by multiple court challenges and the prospect of trade battles that have been exacerbated by the imminent return of President Donald Trump to the White House.”

So, as it stands right now, we have a bill aimed at trying to force streaming giants to promote Canadian content, regardless of domestic demand for it, while at the same time aggravating our largest trading partner in the process, whom we are on the verge of a trade war with.

Is the Online Streaming Act worth the paternalism and the costs? Absolutely not.

This article was made possible by the Digital Media Association and the generosity of readers like you. Donate today.