Did you know there’s an election in Alberta?

With headlines dominated by the teachers’ strike, tariffs, pipelines, and Canada’s place in the world, it’s easy to forget that voters across Alberta’s cities, towns, villages, and municipal districts are just days away from picking their next civic officials.

Admittedly, it’s been a bit of a snooze fest.

Even in Calgary and Edmonton, where party politics have seeped into local campaigns, turnout could end up being among the lowest in years. The limited polling available suggests many urban voters still don’t know who they’re voting for.

Folks can be forgiven for feeling a little election fatigue.

Even in less pressing times, municipal issues often get sideswiped as less important—too granular, too petty, too much about zoning and bylaws. But no other level of government offers services so directly tied to our daily lives.

They include the roads we drive, the buses we take, the safety of our streets, the snow that gets cleared, the water and utilities that keep our homes running, the parks where our kids play, and so much more.

In fact, the federal government can shut down for a week, and our lives would likely go on business as unusual. Ottawa arguably doesn’t offer many direct services.

The provincial government hits closer to home with its jurisdiction over health care, education and natural resources.

But it’s municipal governments that shape the texture of everyday life. If a city were to shut down for even one hour, there’d be chaos with 911 calls going unanswered, traffic lights blinking red, first responders not responding, and light-rail trains stalling midway between stations.

And at no other level of government are our taxes so directly tied to the services we receive.

It’s also the level where residents are often the most vocal. That might be because your property tax bill arrives by mail, with your name on it, and the money comes straight out of your bank account.

Property taxes and affordability

The few thousand dollars we remit every year feel tangible—unlike the much larger share of income taxes automatically skimmed off our paycheques by higher levels of governments.

That’s not a bad thing. It keeps us engaged and gives us reason to demand transparency.

And this year, the cost of living debate is colliding squarely with property taxes.

People cool off in the city hall pool in Edmonton Alta, on Wednesday June 30, 2021. Jason Franson/The Canadian Press.

Municipalities can’t run deficits. Each year, city hall tallies what it needs to spend, then divides that total by the combined value of all assessed properties (residential and commercial) within its jurisdiction. This simple formula—budget divided by assessment base—determines the annual tax rate.

It’s why the number on your property tax bill changes every year. It rises and falls not just with your home’s value, but with how much the city decides it needs to spend.

Underneath all the debates about crime, rezoning, and political branding, a major undercurrent in Calgary and Edmonton is about affordability, and whether people still believe they can build a life here.

For younger voters, that question feels especially urgent. In one local news report, not a single young person under 25 brought up blanket housing rezoning as an issue, even though it has dominated the campaigns.

They talked instead about the cost of food, housing, and about the challenges of finding good jobs.

That anxiety around making ends meet cuts across generations. Older homeowners feel it too, as they watch their property tax bills rise faster than their wages and what their properties are worth.

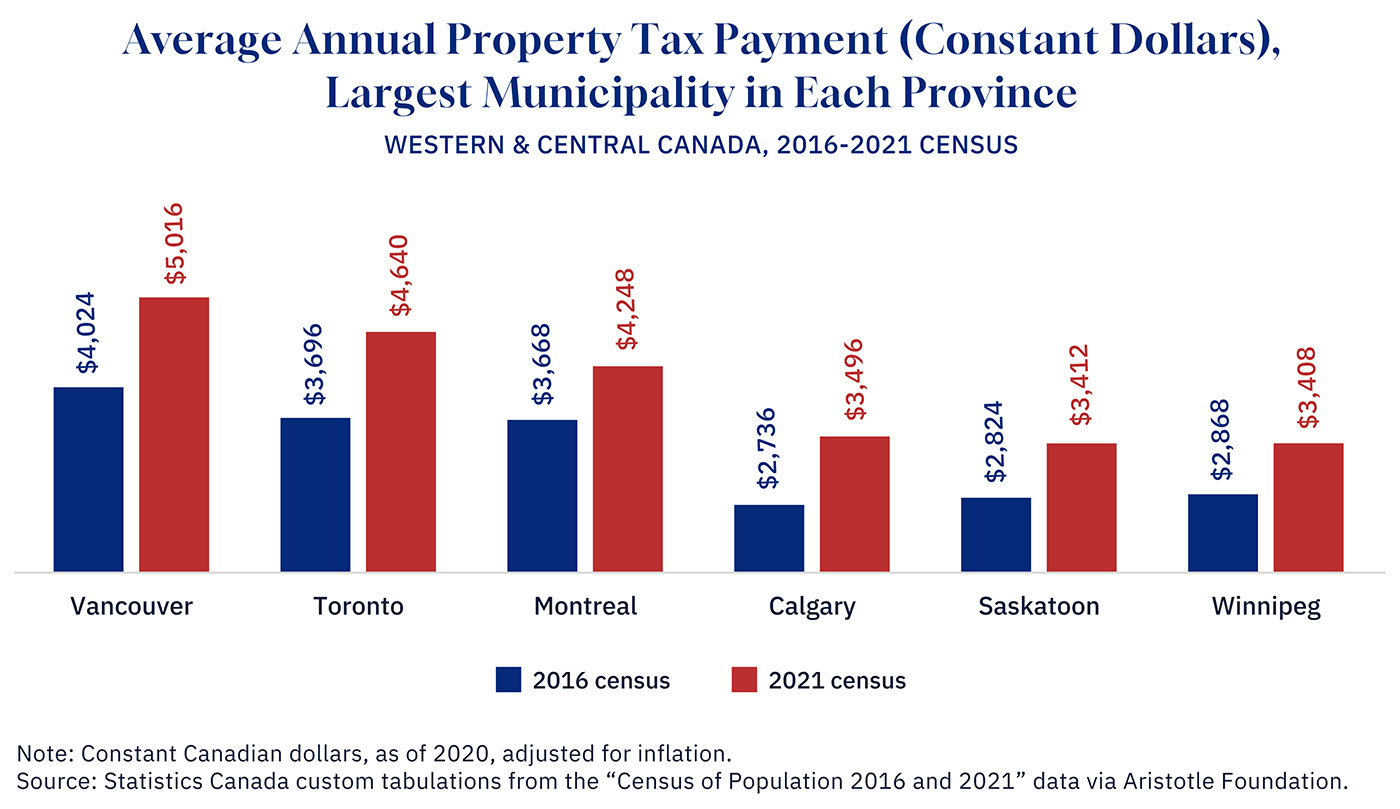

A new report from the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy puts numbers to that feeling. It finds that from 2016 to 2021, Calgary’s average property tax bill climbed 28 percent—from $2,700 to nearly $3,500—while the overall tax burden on households relative to income rose 47 percent, the sharpest increase in the country.

In other words, people are paying more for less.

Squeeze on homeowners

The foundation calls Calgary an “outlier city”—one where declining property values and income collided with rising municipal budgets during the studied census periods.

On the commercial side, Calgary’s downtown office market is still finding its footing. Leasing activity has picked up a bit, but by the end of the second quarter of 2025, the city still saw about 230,000 sq. feet of negative absorption—meaning more space went empty than got filled.

The downtown vacancy rate now sits at nearly 28 percent.

Any shortfall in non-residential taxes has to be made up elsewhere, and for far too long, much of that burden has fallen on businesses that continued to operate.

This problem dates back nearly a decade to the deep recession of 2015-16, when Calgary’s business tax base collapsed alongside oil prices. For years, city council delayed a full reckoning, using reserves and temporary rebates to soften the blow.

Eventually, a meaningful shift to higher residential property tax rates became unavoidable.

But the squeeze on homeowners is nothing to sneeze at either, with pressures coming from multiple fronts.

An increase in the provincial education tax this year, for example, means around a third of property taxes from both Edmonton (30 percent) and Calgary (37 percent) now go straight to provincial coffers.

Add it all up, and the Alberta “advantage” is starting to look less attractive.

In the Aristotle Foundation report, the average homeowner in Toronto paid roughly $4,600 in 2021 in property taxes on a comparable home value. In Vancouver, it was more than $5,000. Calgary’s average bill at nearly $3,500 is still lower, but no longer dramatically so.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Source: Statistics Canada.

In fact, the report warns of a potential “vicious spiral” where the more income and property values drop, the more enticing it is for council to raise taxes.

Another tempting fix is to raise fees, which are separate from property taxes. That means higher costs for business permits, parking, transit, and utilities—maybe even more of the so-called “stupid taxes,” like speeding tickets.

It’s a quick way to spread the cost of city services across more people, including visitors. But fee hikes are limited in scope, and are never popular. They can also be quite punishing for low-income individuals who rely on buses, libraries, and other public amenities.

Long-term solutions are not easy

The harder, longer-term answer is to curb municipal spending. Fiscal hawks have long called for cities to go back to the basics and stop meddling in things like social advocacy and pilot projects.

But the even harder, longest-term answer, is to grow the local economy.

If Alberta’s big cities want to stay vibrant in the long run, the real solution lies in creating the conditions for wealth generation. That means making cities places where people want to build businesses, live, and invest.

The good news is, people are already moving here in droves. Now we need to encourage them to take chances and become innovators in order to perpetuate the Alberta advantage that attracted them here in the first place.

It means faster permitting, predictable zoning, fewer restrictions, expedited and coordinated construction, safer communities, fewer disruptions, reliable infrastructure, more entrepreneurial thinking—even some beautifying—policies that attract employers and businesses instead of driving them away.

So these elections really are largely about bylaws and zoning, after all. Yikes.

Ultimately, cities can’t tax or cut their way to prosperity. They have to earn it by being magnets for opportunity.

Because when cities stop for even an hour, all hell breaks loose. That’s reason enough to make sure they can thrive.

Municipal elections often feel 'under-the-radar.' Why are these local votes so crucial for our daily lives?

The article links rising property taxes to affordability issues. How does this 'squeeze on homeowners' impact Alberta's economic outlook?

Beyond cutting spending, what's presented as the 'hardest, longest-term answer' for municipal prosperity in Alberta?

Comments (0)