Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer attracted significant attention and headlines last week with a report on Canada’s economic and fiscal outlook.

He didn’t mince words, calling the federal situation both “shocking” and “unsustainable.”

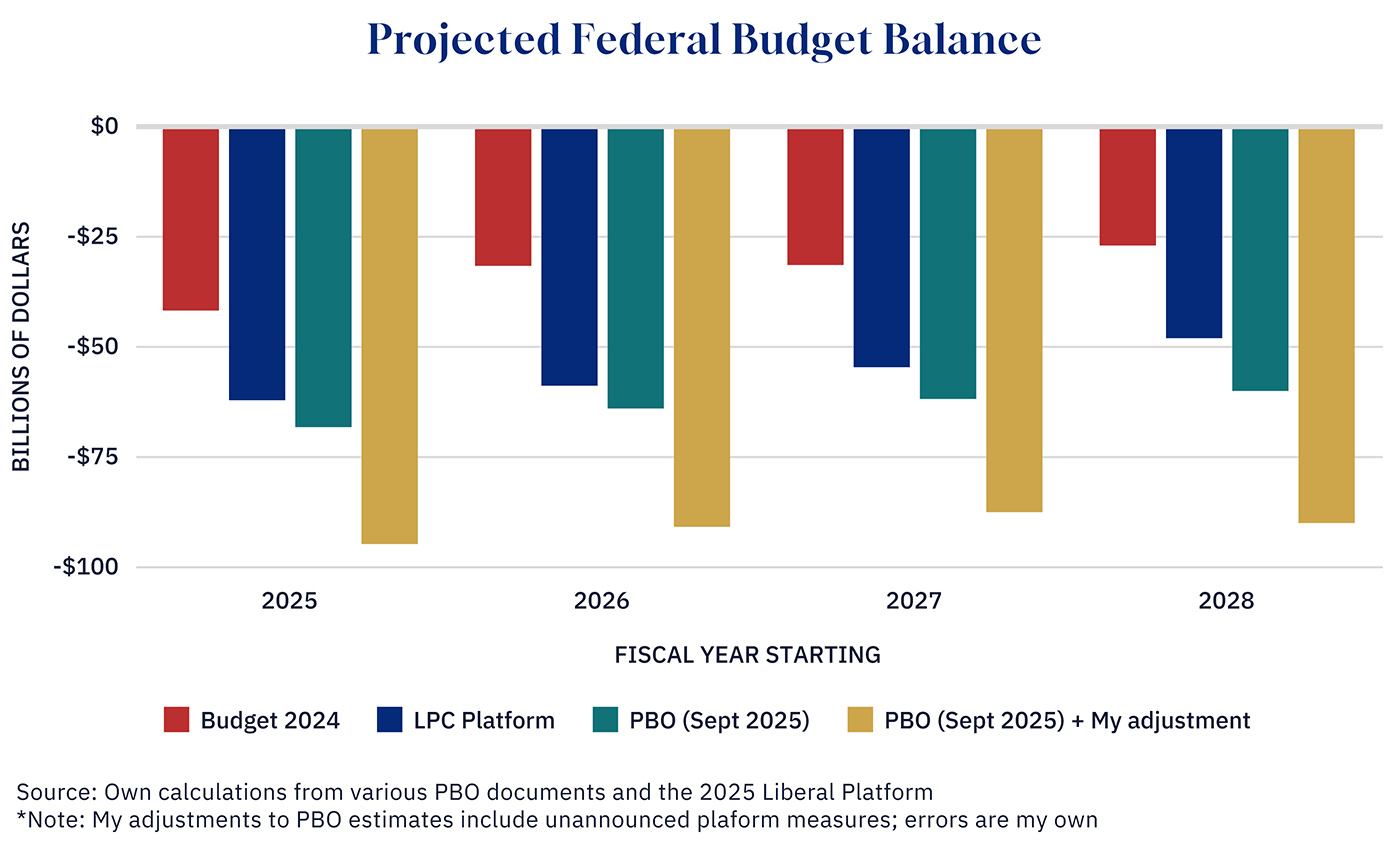

The PBO analysis found that the federal budget deficit will grow beyond previous projections. From the total of just over $132 billion between 2025 and 2028 that was projected in Budget 2024 to the nearly $255 billion now projected for those years.

Much of this is driven by a considerable decline in federal tax revenues (from the personal income tax cut and other measures), as well as even larger increases in federal program spending. Total operating spending alone (excluding many federal transfers) is projected to be more than $10 billion per year higher than previously anticipated.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

And it gets worse. These projections don’t count many of the government’s own campaign platform commitments, including increases in military spending. Adding unannounced measures back into the PBO estimates, I find cumulative deficits over the next four years exceed $360 billion—almost triple what last year’s budget anticipated.

A larger deficit means increased borrowing and rising interest costs. The PBO projections indicate that interest costs alone may consume 14 cents of every dollar in government revenue by 2030, or nearly 16 cents of every dollar in taxes. That’s roughly double where we were before the pandemic and the highest in nearly two decades.

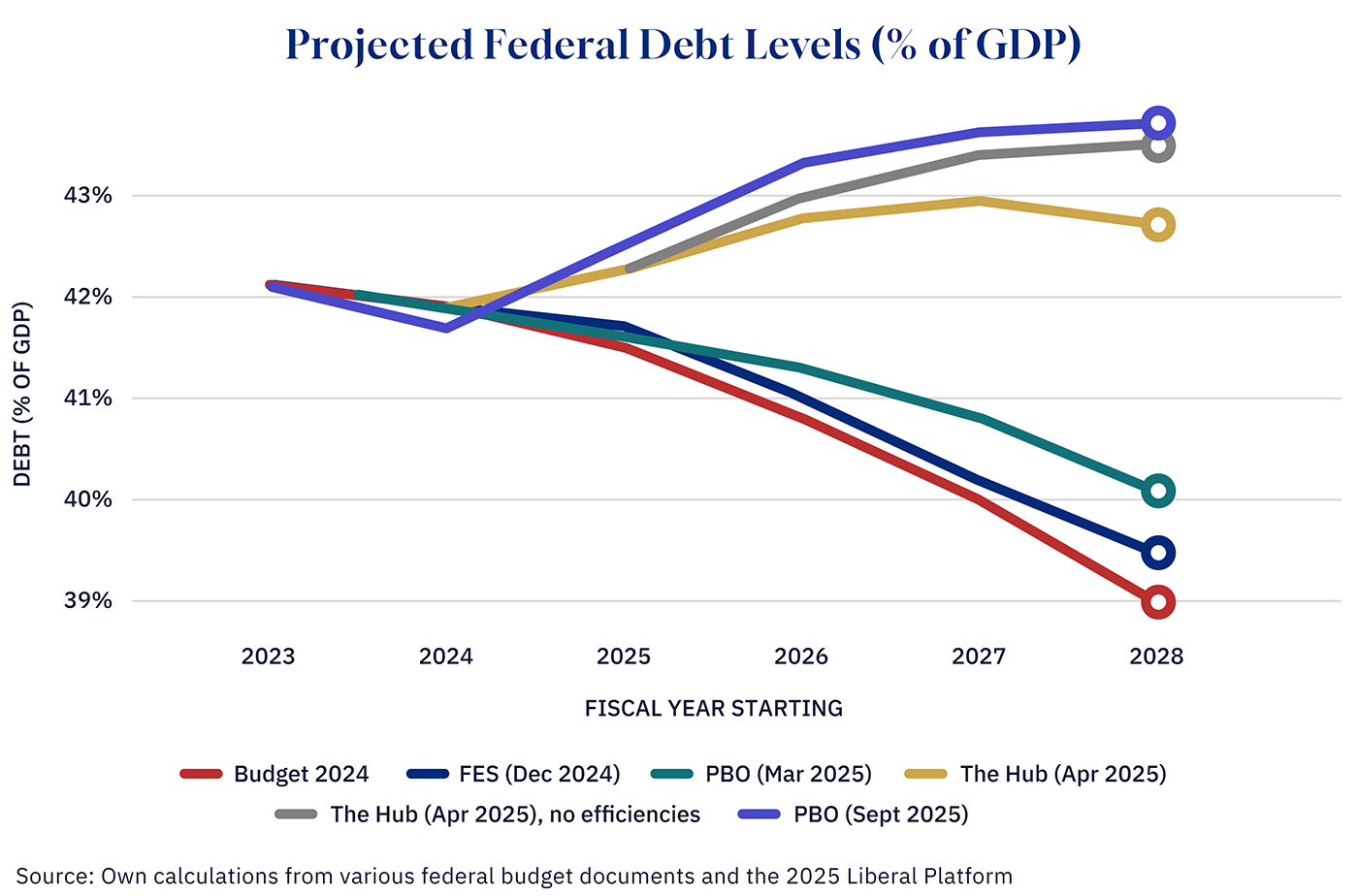

But even more concerning is that federal debt is set to grow at a faster rate than the economy. In testimony to a parliamentary committee last week, the PBO noted that this was the first time in 30 years he had seen a projection where this key measure of fiscal sustainability continued to rise over time.

Simply put, federal finances are at a precipice.

Warnings we’ve heard before

The PBO is right to raise these concerns. It’s a critical part of their mandate. But we’ve long known of these problems. The C.D. Howe Institute released a report from Don Drummond, Alex Laurin, and Bill Robson last July, for example, with their own estimates for the 2025 to 2028 cumulative deficit reaching nearly $343 billion. Very close to my estimate here that adjusts the new PBO projections.

The unsustainable federal debt trajectory is also not new. Back in April, I wrote here in The Hub that the Liberal platform represented a sharp departure from even the already weak fiscal rules of recent years. In that piece, I projected that, by 2028, federal debt would reach 43.5 percent of GDP—assuming the government’s hope of finding efficiencies was unsuccessful. The PBO now estimates federal debt will rise to 43.7 percent by that same year—again, not including many new measures committed to in the platform.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

This is the budget warning that Canadians cannot ignore.

The upcoming budget, set to be released on November 4, will reveal whether the government has a new plan—complete with clear fiscal anchors—to shift off this unsustainable path.

Global debt risks

Canada is not alone in facing long-term fiscal challenges.

The United States is in a particularly difficult position, with its entire Social Security trust fund projected to be depleted by the early 2030s.

European countries also face mounting fiscal pressures, with much of the pressure there driven by the cost of aging populations—rising pension obligations, increased health-care spending, and greater demands for long-term care.

For perspective, analysts typically measure fiscal sustainability by estimating how much revenue must rise—or spending must fall—to stabilize public debt over time. While results depend on assumptions and modelling choices, the EU estimates that its member countries would need adjustments worth roughly 3 percent of GDP. In a Canadian context, that’s equivalent to increasing the GST from 5 percent to 15 percent.

Fortunately, such dramatic steps are not required in Canada—at least not federally. Provinces are another story, with adjustments on the order of 2 percent or more required for many.

Of course, being in good company is no comfort. If anything, widespread global indebtedness means the risks we face are larger. A debt crisis or financial disruption abroad could quickly spill across borders, making growth here more volatile. All the more reason for Canada to ensure our own fiscal house is in order—so we’re resilient and prepared for the shocks that may come.

Why rules matter

There’s no need for dramatic and immediate action. But there is an increasing need for a longer-term perspective with a clear emphasis on sustainable finances.

That means enacting clear, precise, and actionable fiscal rules to guide policy choices over time. Research, including recent IMF work, shows that strong fiscal rules, when properly enforced, can help not only prevent long-term challenges from mounting but also lower borrowing costs today, as markets price in lower risks.

Canada already benefits from having a strong and independent fiscal watchdog in the PBO.

But what Canada lacks is a clearly defined fiscal framework—a set of rules and timelines to guide policy over time. The previous commitment to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio over time was overly vague, but at least it existed. Today, even that appears to be slipping.

What might a concrete set of rules look like? Alberta may offer the clearest example of a detailed fiscal framework designed to support long-term sustainability. While it has yet to be fully tested, and there are strong critiques of it, it outlines how spending and revenue choices should evolve when the government finds itself in a deficit.

Whatever the details, precise, simple, and transparent rules are essential—especially today.

Canada’s fiscal challenges are growing, though they remain manageable. The PBO’s warning underlines how quickly circumstances can shift, with rising debt bringing higher interest costs, fewer policy options, and greater exposure to global shocks.

But the real danger lies not only in the growing size of today’s deficit, but in failing to plan prudently for what comes next.

Comments (0)